![]()

BORDER COLLIE COUSINS

THE HERDING DOGS OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND

Above, "Storm Clouds" by Edgar Barclay (1842-1913)

INTRODUCTION TO THE HERDING BREEDS OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND

In order to understand the herding dogs of Great Britain and Ireland, we also need to understand the history of these islands, as well as the nature of the wool industry in England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Here we are speaking primarily of the Middle Ages, because that was the period that saw the development of the old working collies that were the direct ancestors of the modern collie breeds of Great Britain and Ireland, and subsequently the collie breeds of North and South America, and of Australia and New Zealand.

The Romans invaded Britain twice, once in 55-54 BC, and again, more successfully, in 43 AD, when the Celtic tribes were defeated or pushed further north and west over a period of about 30 or 40 years. Britain came under increasing attacks from Germanic tribes beginning in the 4th century, and Rome had begun to withdraw. Tradition has it that by the early-to-mid-5th century, Rome had completely abandoned Britain. By 600 AD, the Saxons occupied Lowland Britain.

The Romans brought sheep and sheepdogs with them and were known to have a well-organized wool textile industry in Britain ["The History of Sheep Breeds in Britain" by Michael L. Ryder, Agricultural History Review, December 1964]; however, when they arrived, there was already a wool industry in place. There is no reason to believe that this economy died with the Roman withdrawal. On the contrary, archaeological evidence points to an increased presence of sheep during the Anglo-Saxon period ["Sheep, Horses, Swine, and Kine: a Zooarchaeological Perspective on the Anglo-Saxon Settlement of England" by Pam J. Crabtree, Journal of Field Archaeology, Boston University, Summer 1989]. So, while the end of the Roman period may have caused the wool industry to stagnate to a certain extent, and the invading Germanic tribes may have decimated it at first, Britain's wool industry soon recovered and began to expand.

Above, detail from the Bayeux Tapestry, that tells the story of William the Conqueror's

journey from Normandy to England and the defeat of the English.

There are a number of dogs depicted in the Tapestry,

but it is more likely that they are hunting dogs than herding dogs.

England

Dr. Michael L. Ryder [Ibid.], eminent British historian and expert on the history of sheep and wool, says that "sheep were more important during the Anglo-Saxon period than [has] hitherto been realized...The ubiquity of sheep is clearly shown by the many Saxon place names" in England--Shepley (which literally means 'a clearing or meadow where sheep are kept'), Shapwick, Shepperton, Shepton, Shepreth, Isle of Sheppey, Shipham, Shipton, Shipley, Shiplake, Shiplate--to name a few.

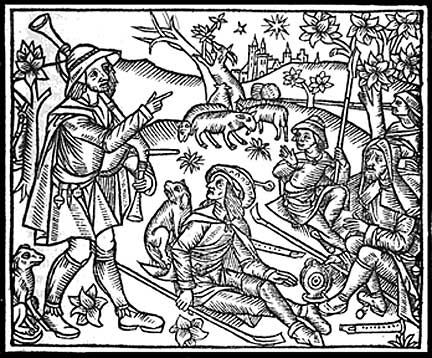

Left, an illustration from Le Compost et Kalendrier de Bergiers, a fore-runner of the perennial almanac. First published in Paris, it was translated into English in 1503 as The Kalender of Shepherds, and ran for at least 17 more editions. This illustration shows the shepherds gathering in a field with their dogs. One of them is pointing at the sky, where there is a comet, likely to be heralding the birth of Christ.

Left, an illustration from Le Compost et Kalendrier de Bergiers, a fore-runner of the perennial almanac. First published in Paris, it was translated into English in 1503 as The Kalender of Shepherds, and ran for at least 17 more editions. This illustration shows the shepherds gathering in a field with their dogs. One of them is pointing at the sky, where there is a comet, likely to be heralding the birth of Christ.

According to Eric Kerridge, a British historian on economics and agriculture, "[A]t the end of the seventh century, England was making woollen cloth as an ordinary commodity for the local communities. By the second half of the eighth century, however, there is clear evidence that English woollens were being exported to the Continent" ["Wool Growing and Wool Textiles in Medieval and Early Modern Times" by Eric Kerridge, The Wool Textile Industry in Great Britain, edited by J. Geraint Jenkins, 1972, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London].

Kerridge goes on to say: "In Britain...wool has been grown for the most part as a joint product with manure and meat...In the characteristically English sheep-and-corn husbandry, the flocks were fed upon the downs, wolds, heaths, hills and other sheep-pastures during the day and then close-folded on the tillage by night, that they might consolidate it by their tread and fertilize it with their urine and droppings..."[ibid.].

This would have required twice daily movement of sheep and it seems inconceivable that it could have been achieved without the use of herding dogs.

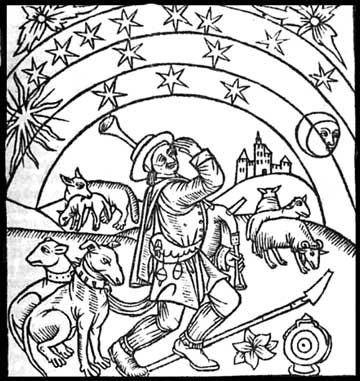

Right, another illustration from The Kalender of Shepherds. This one shows a single shepherd (a bagpipe is often used in Medieval drawings as associated with shepherds) with his two dogs on lead. They are wearing spiked collars, presumably to protect them from wolves. A comet appears in this one as well.

Right, another illustration from The Kalender of Shepherds. This one shows a single shepherd (a bagpipe is often used in Medieval drawings as associated with shepherds) with his two dogs on lead. They are wearing spiked collars, presumably to protect them from wolves. A comet appears in this one as well.

By the Middle Ages the bear had been eliminated from Britain, but the wolf remained, so sheep guardian dogs were also necessary. Robert Leighton writes, "In Anglo-Saxon times every two villeins were required to maintain one of these [English Mastiff] dogs for the purpose of reducing the number of wolves and other wild animals." [Dogs and All About Them by Robert Leighton, Castle and Company, Ltd., London, 1910.]

For the most part, we rely on the archeological record for information about dogs in the Middle Ages; however, the record can't really tell us what type of dog has been found. About ten years ago, a large Anglo-Saxon village more than 100 acres in size was excavated in the fens of North Cambridgeshire. It had been inhabited from the 7th through 12th centuries. Among the 50,000 artifacts and bones found were the graves of about 20 dogs, possibly sheepdogs. Their careful burial was in stark contrast with the random dumping of other animals, such as cattle, sheep, pigs, and cats. ["In Brief: Saxon Village", Simon Denison, editor, British Archaeology, December 1999.]["East Anglian Fenland Village Discovered", Michelle Ziegler, editor, Archaeology Digest, Summer 2000.]

Left, a small illustration from The Kalender of Shepherds, showing a shepherd about to shear his sheep.

Left, a small illustration from The Kalender of Shepherds, showing a shepherd about to shear his sheep.

There is very little reference to dogs at all in the written records of the Middle Ages. One source that does mention them is Aelfric's Colloquy. Aelfric of Eynsham (c. 955-1010) was an English Benedictine monk and abbot, and a prolific writer in Old English and Latin. The Colloquy was a dialogue, designed to serve as a manual of proper conversation in Latin for his students. In it, the master addresses his students one by one. Each takes the part of a particular laborer (e.g., a plowman, a shepherd, a butcher, etc.) and talks about his job. Here, the shepherd speaks:

"In the early morning I drive my sheep to their pasture, and in the heat and in cold, stand over them with dogs, lest wolves devour them; and I lead them back to their folds and milk them twice a day, and move their folds..." [Farming in the First Millenium AD: British Agriculture Between Julius Caesar and William the Conqueror by P. J. Fowler, Cambridge University Press, 2002.]

There is no specific mention of a herding or driving dog in the Colloquoy, but it seems likely that the shepherd would have needed the assistance of such a dog if he moved his sheep two or three times a day, every day, in every weather.

There is, of course, much more to English history in the Middle Ages than just the Anglo-Saxons, but much of it is beyond the scope of this article. It was the Anglo-Saxons who had the biggest impact on England, historically, linguistically, and genetically. However, we will touch on the other contributing cultures. The Celts and the Vikings will be discussed in connection with Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, below. The Norman Conquest had the most effect on England.

Left, another detail from the Bayeux Tapestry.

Left, another detail from the Bayeux Tapestry.

According to Ryder, the Domesday Book, the record of a great survey taken on behalf of William the Conqueror and completed in 1086, "showed that soon after the Norman Conquest there were more sheep than all other livestock put together...[and a] hundred years after the Domesday survey the sheep had increased [even more] in importance."[Ryder, ibid.] By the 12th century, wool was England's most profitable export.

Normans penetrated the upper echelons of society, and their culture affected English laws and system of government. Their language had an influence on English in the form of borrowed words and language development, but Norman French was not adopted by the populace at large, and language is what truly defines a people. Furthermore, the Normans were descended from Danish Vikings who were given feudal overlordship of areas in northern France in the 8th century; and Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king, also had Danish ancestors. So, although history and the Bayeux Tapestry makes the Norman Conquest seem enormously important, in terms of who the English really are it was not as significant as history would like us to think. History is written by the victors.

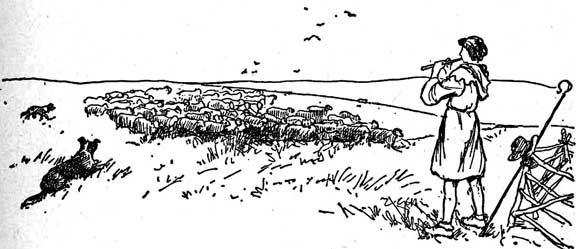

Above, an illustration from The Wool Pack by Cynthia Harnett

It might be helpful in looking for the shepherd's dog in the Middle Ages to examine the work of a modern author. Cynthia Harnett (1893-1981) was a highly acclaimed English writer and illustrator of children's historical fiction. In 1951 she wrote a novel called The Wool-Pack [Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1951]. It was set in 15th century Cotswolds and is about the English wool trade at its height. There is a scene where the protagonist, Nicholas, and his shepherd friend Hal, gather a sheep flock that has been scattered by a stray dog. They use two sheepdogs, Rolf and Fan, to round up the sheep, and a Cotswold rhyme for counting the sheep to make sure that none are missing.

" '...[H]is plaguey dog scattered the sheep'...said Hal contemptuously...'We must get them in quickly or they will be half across the parish. Do you take Fan and go up the hill, and I will go down with Rolf.' "In their fright the sheep had indeed strayed far and wide. Hal's reed pipe was kept busy guiding the dogs. 'Go seek, go seek.' 'Hold! Hold!' 'Fetch them in, fetch them in.' Fan and Rolf knew the notes as well as Nicholas did. They guided the flock into the fold through a gap in the stone wall, and Hal counted as the sheep passed in, using his father's own special tally rhyme... "When Hal was satisfied that none of the sheep were missing they closed the gap in the fold with hurdles."

Ms Harnett calls the dogs "collies". Because of her reputation for exceptional attention to detail and meticulous background research, we can probably take her word for it, that at least some herding dogs in the Late Middle Ages were actually collies. But was the word "collie" used for the shepherd's dog by the Late Middle Ages?

Above, an illustration from the 15th century manuscript, the Scotichronicon of Walter Bower

depicts one of the foundation myths of Scotland. It shows Scota with Go’del Glas, voyaging from Egypt.

Scota was supposedly the daughter of an Egyptian pharaoh and from whom the name "Scotland" derives.

Goídel Glas was credited as the creator of the Goidelic languages of Irish and Scottish Gaelic, and the eponymous ancestor of the Gaels.

In one version of the myth, Scota and Goídel Glas are wife and husband.

Ireland and Scotland

I am grouping Ireland and Scotland together because, during the Middle Ages, Scotland was peripheral to Roman Britain and its history has more in common with that of Ireland and Scandinavia than with England. By 200 BC Celtic migration had come to dominate Ireland. When you think the Celts arrived in Scotland depends upon whether you consider the Picts a Celtic race, you believe the Scottish foundation myth of "Scota and Goídel Glas", or you count Scotland's inception from the arrival of the Celts from Ireland in roughly the 6th century. By the early Middle Ages there was a Celtic presence in both Scotland and Ireland.

Celtic society was based almost entirely on pastoralism and the raising of cattle or sheep. The importance of cattle to a transhumant society created a Celtic institution: the cattle-raid, which was immortalized in the Irish fable, the Táin Bó Cualingne ("The Cattle Raid of Cooley") ["European Middle Ages: the Celts" by Richard Hooker, Washington State University, 1996, World Civilizations]. As in Ireland, most people in Scotland were occupied with subsistence farming and pastoralism. A few arable areas allowed for good grazing all year round. In places where arable land was scarce, smaller, uninhabited islands were used to graze sheep.

Were there sheepdogs in Ireland and Scotland in the Early Middle Ages? There may have been--must have been--but we have little information available to us from this period.

There were Saxon settlements in the south and east of Scotland, and the Anglo-Saxon or Old English language was the major factor in the development of the Lowland Scots language. In Ireland, and in the west of Scotland, Gaelic prevailed as the dominant language. There were relatively small scale settlements of both the Vikings and Normans in the Middle Ages in Ireland; however the so-called "Norse-Gaels" dominated the Irish Sea and western Scotland. They were people who had originated in Viking settlements in Ireland and Scotland, were strongly influenced by or married into Gaelic culture, and plied the Irish Sea, settling along the coasts and in the Western Islands. Somerled was one of these and he founded a dynasty which became the Lords of the Isles.

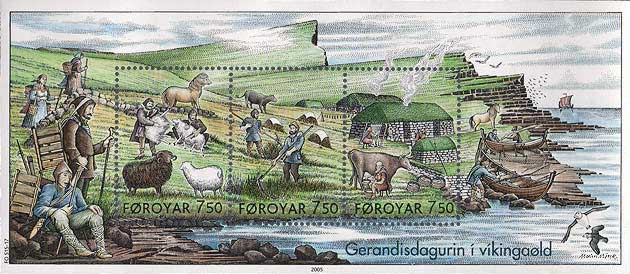

Above, a Faroese stamp showing an artist's rendition of what a Viking farm would have looked like in the Faroe Islands.

It would have looked pretty much the same in Iceland, Greenland, and the Shetland and Orkney Islands during the early Middle Ages.

The period from the earliest accounts of Viking raids in the 790s until the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 is commonly known as the Viking Age. Genetic studies in the British Isles have shown that the Vikings settled there as well as raided there. Viking navigators opened the seas to new lands to the north, west and east, resulting in independent settlements in Shetland and Orkney. Generally speaking, the Norwegians expanded to the north to Scotland and west to Ireland, the Danes to England and France, settling in the Danelaw (northern/eastern England) and Normandy.

Left, an artist's drawing of a Viking shepherd, rescuing his sheep in a snow storm. Note the dog of a spitz-type behind him.

Left, an artist's drawing of a Viking shepherd, rescuing his sheep in a snow storm. Note the dog of a spitz-type behind him.

Olaf Tryggvason was King of Norway from 995 to 1000. He was born in Norway, and spent a good part of his youth in Novgorod (Russia) which was a Viking city at the time. After leaving Novgorod, Olaf began raiding in Germany, and later in the Hebrides and England. In 988 Olaf married the King of Dublin's sister (Dublin being a Viking settlement) and they divided their time between England and Ireland. Olaf Tryggvason's Saga, one of the great Icelandic tales which tell the story of the Vikings, tells this tale about Olaf:

"When Olaf was in Ireland he went on a coast-raid. As they needed provisions they went ashore and drove down many cattle. A bondi [a freeholder or bondsman] came there and asked Olaf to give him back his cows. Olaf replied that he might take them if he could recognise them and not delay their journey. The bondi had with him a large sheep-dog. He pointed out to it the herd of cattle, which numbered many hundreds. The dog ran through all the herds, and took away as many cows as the bondi had said belonged to him, and they were all marked with the same mark. Then they acknowledged that the dog had found out the right cattle. They thought it a wonderfully wise dog. Olaf asked if the bondi would give him the dog. 'Willingly,' answered the bondi. Olaf at once gave him a gold ring, and promised to be his friend. The dog's name was Vigi, and it was the best of all dogs. Olaf owned it long after this." ["Occupations and Sports of Men" by Paul B. Du Chaillu, The Viking Age: The Early History, Manners, and Customs of the Ancestors of the English-Speaking Nations, Vol. II, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1890.]

Right, this would have been the type of sheep, called Northern Short-Tailed, that the Vikings would have brought with them. Many of the small, British so-called "Primative Breeds" (like the Hebridean, the Manx Loghtan, the Shetland, and so forth) are decended from this type of sheep.

Right, this would have been the type of sheep, called Northern Short-Tailed, that the Vikings would have brought with them. Many of the small, British so-called "Primative Breeds" (like the Hebridean, the Manx Loghtan, the Shetland, and so forth) are decended from this type of sheep.

Where the Vikings made their greatest impact was in Shetland and Orkney. Andro Linklater, writing about Shetland, says: "According to Egil's Saga...the first Norsemen came to Shetland seeking land...[T]hey sailed from Scandinavia across the North Sea towards the setting sun in search of a place to cultivate crops and raise animals...and just as the legend of the American West was to glorify the gunfighter and ignore the cowhand, so the sagas are filled with the deeds of warriors rather than of farmers. In each case, the reality was that herding and ploughing left a deeper mark than shedding blood." ["Eden with Weather: A Short History of This Valiant Place" by Andro Linklater, Shetland Breeds, Little Animals, Very Full of Spirit, Ancient, Endangered & Adaptable, Posterity Press, Inc., USA., 2003.]

Writing in the same book, James R. Nicolson tells us: "After the change from Norse rule to Scottish rule in the 15th century, regulations governing the keeping of sheep were laid down in the Country Acts of Shetland...[I]t was unlawful for anyone to trespass on a neighboring... common grazing ground...with a sheepdog unless accompanied by one or two neighbors who were regarded as 'famous honest men'. If this rule was broken the trespasser would be liable to a fine of six pounds in Scots money; the dog would be hanged." ["Shetland Sheep, A Wealth of Wool and Words" by James R. Nicolson, Ibid.]

A very cruel sentence for the dog, but indicative of how valuable a sheepdog was. The loss of such an important asset would be a convincing deterrent. Nicolson goes on to explain the reason for this ruling:

"[T]he native sheep were not herded in docile flocks at that time but ran wild and had to be caught by specially trained hadd dogs (from the old Scots word hald meaning 'grasp'). These dogs ran down and held each sheep individually. For this reason it was made illegal to go through a neighboring [sheep common] with a dog without reliable witnesses. "It was also decreed that no one should keep a dog unless authorized to do so. This regulation was designed to prevent people from removing the wool from a sheep belonging to others, since ownership of the wool could not be established after it had been removed from the sheep...."[Ibid.]

Dogs still worked like this well into the 20th century in the Faroe Islands, which is thought to have been settled by Norsemen from Shetland and Orkney rather than directly from Scandinavia.

Below, a sheepdog working on the Faroe Islands in 1970.

["The Faeroes, Isles of Maybe" by Ernle Bradford (author) and Adam Woolfitt (photographer),

National Geographic, September 1970.]

A reproduction of a Welsh farmstead from the Middle Ages.

Wales

Wales is likewise a Celtic land, and a distinct Welsh national identity emerged in the early 5th century, after the Roman withdrawal from Britain. In the highlands of Wales, the Welsh culture was typified by continuity [The Agrarian History of England and Wales by Joan Thirsk and Edward Miller, Cambridge Univerity Press, 1991]. In these areas, pastoralism prevailed. Distinctive mountain breeds of sheep developed in the Welsh Mountains. The people were fiercely independent. The word Cymry, referring to the country, first appeared in a poem dating to 633. By 700, the people referred to themselves as Cymry, the country as Cymru, and the language as Cymraeg. The words "Wales" and "Welsh" are of Saxon origin [Wikipedia].

The Anglo-Saxons made little headway into Wales except in the northeast along the border with England. The Vikings settled the coastal areas. But the vast, impenetrable, mountainous center of the country remained Welsh and Celtic.

Writing for the World Conference on Records in 1980, J. Geraint Jenkins said:

"The laws of the medieval Welsh king, Hywel Dda [Howel the Good, 880Đ950] depict a semi-nomadic people with strong tribal affinities, practicing a pastoral economy. From the 11th century the numerous Welsh princes attempted to settle these nomadic pastoralists in permanent homesteads. The unit of landholding in medieval Wales was that of a gwely ("bed"), which was an association of people bound together by blood relationship...Small plots adjacent to the dwelling were enclosed for crop growing, while rather larger enclosures for herding animals were to be found farther away from the homestead. As time progressed, the existing land was subdivided among the kin group...The continued subdivision of property meant smaller and more scattered holdings...Uplands and moors were widely used in the Middle Ages for summer grazing; with increasing demand for land...many of these hafodai ('summer dwellings') became permanent farmsteads." ["Life and Traditions in Rural Wales" by J. Geraint Jenkins, World Conference on Records, 1980, Salt Lake City, Utah, from FamilySearch.org, a website of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]

These same laws "gave the worth of an efficient herding dog as that of an ox in its prime."[20] Two extinct types of herding dogs from Wales, the Welsh Hillman and the Welsh Black & Tan, are considered by some to have been descended from ancient herding and hunting dogs of Wales ["Herding Dogs in Britain & Ireland Part III: Extinct Types in Wales" by Barbara Carpenter, The Shepherd's Dogge, Fall 1994]. The Welsh Corgi is likewise thought to be of ancient origin. There may have been others, for example, the ancestors of some of the Welsh Sheep Dogs of today. We'll hear more about these dogs in a later installment in this series.

Copyright © 2014 by Carole L. Presberg

Return to

![]()

BORDER COLLIE COUSINS

THE OTHER WEB PAGES WE MAINTAIN

These web pages are copyright ©2014

and maintained by webmeistress Carole Presberg

with technical help from webwizard David Presberg

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

If you are interested in using ANY material on this website, you MUST first ask for permission.