![]()

THE HISTORY OF THE SHEPHERD'S DOG

Above, the Shepherd's Dog from Chambers's English Readers Book, edited by J.M.D. Meiklejohn, W & R Chambers, London 1878

THE SHEPHERD'S DOG IN THE MIDDLE AGES

[Please visit our History of the Shepherd's Dog Glossary for definitions of terms used in these articles]

The Middle Ages or medieval period is generally considered to have taken place from the 5th century through the 16th century. The shepherd's dog was slightly more apparant in the Middle Ages than it was in Antiquity. Nevertheless we still needed to be a sleuth in order to tease out the facts. One of the best sources of information on shepherd's dogs in the medieval period comes, perhaps surprisingly from the artwork associated with religious manuscripts.

FROM RELIGIOUS SOURCES

Above, an illustrations from the Book of Kells, showing what looks like two dogs. The one on the left looks like it could be a mastiff, and thus a sheep guarding dog; and the one on the right looks as if it might be a shepherd's dog, though, like most of the illustrations from the Book of Kells, it is open to interpretation.

The Book of Kells

ca. late 6th through early 9th centuries

Left and right, details of the two dogs mentioned above.

Left and right, details of the two dogs mentioned above.

The Book of Kells [Sir Edward Sullivan, The Book of Kells, The Studio Ltd., London, 1920] is possibly the most famous Western religious resource. It is a group of manuscripts produced in monasteries in Ireland, Scotland and England, and in monasteries on the Continent linked to Irish or English monastic traditions. It was housed in the Abbey of Kells in County Meath, Ireland, for most of the medieval period, whence commeth its name. It is beyond this article to go deeply into the contents of the Book of Kells, but I have examined some of the illustrations for references to dogs, however unlikely that might be.

Regarding the "Portrait of Virgin and Child" in the Book of Kells, and the opinion of some writers that the Virgin's throne terminates in a head of a dog, Sir Edward Sullivan wrote that "The dog in the Bible has a notoriously evil reputation, being 'unclean' under the Old Law, and would hardly have been selected as an ornament for the Virgin's throne. The head can surely be no other than that of the Lion..."[ibid.].

However, these manuscripts were not written and illustrated in Biblical times, and are likely to reflect a more moderate view of the dog. In fact, they were written and illustrated by Celtic monks, and the Celts believed that dogs were the guardians between worlds, between the seen and the unseen. Mistakes in the Book of Kells were celebrated with a drawing of a dog. Judy Balchin points out, "if a word were left out, it would be inserted at the foot of the page, guarded by the drawing of a dog, with an arrow pointing to the error." [Designs From the Book of Kells, Search Press, 2009].

Nevertheless, in the few cases where I was able to make out what might be a dog among the elaborate and contorted designs, I am afraid that there was little to distinguish it as a shepherd's dog. Perhaps more detailed analysis is warranted.

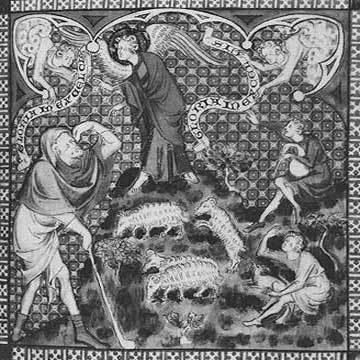

Above, the "Anunciation to the Shepherds" from the Holkham Bible [1].

Note the dog at the center of the picture.

The Holkham Bible

ca. 1320-1330

The Holkham Bible [British Library online] is a "picture-book" rendition of the Biblical stories, written in London in the 14th century. It highlights stories from the Bible in an almost comic-book fashion (similar to the Bayeaux Tapestry), starting with the Creation, through the life of Jesus, to the Last Judgment. There are illustrations of the "usual Biblical characters", but 14th century people and everyday life of 14th-century England are pictured there as well. The book was probably made around the time of Geoffrey Chaucer's birth or a few years before. It was made for a Dominican friar, by a "Cockney London artist" [Michelle P. Brown, Outreach Officer of the British Library], a layman hired to do the job, to help the friar explain the stories to his flock.

The illustrations are accompanied by brief explanatory texts in Anglo-Norman French, the literary language most familiar to contemporary English nobles (rather than Old English (Anglo-Saxon), the language that was spoken by the common people in England at the time). It is called the "Holkham Bible" because it was housed for many years in the library of Holkham House in Norfolk (East Anglia).

The costumes, tools, weapons and buildings in the illustrations are not Biblical, but are those of 14th-century England. They give a near documentary representation of many early occupations such as dyer, smith, carpenter, shepherd and midwife. The original pages are 10 inches high. The pictures are drawn in ink and leadpoint pencil, and partly coloured in wash to give a three-dimensional impression. There are more than 200 scenes in 84 pages.

The costumes, tools, weapons and buildings in the illustrations are not Biblical, but are those of 14th-century England. They give a near documentary representation of many early occupations such as dyer, smith, carpenter, shepherd and midwife. The original pages are 10 inches high. The pictures are drawn in ink and leadpoint pencil, and partly coloured in wash to give a three-dimensional impression. There are more than 200 scenes in 84 pages.

Left, a detail from the "Anunciation to the Shepherds".

The scene of the "Annunciation to the Shepherds" shows a dog likely to be a shepherd's dog [Christopher Howse, a columnist for theTelegraph, December 22, 2007], since the only beings in the picture, besides the angel, are the shepherds, the sheep, and the dog. It took an Englishman who likely saw working dogs bringing sheep to market in London, to include one in a book about the Bible, something that one rarely sees in representations of Biblical stories. It shows that shepherds' dogs were common at the time of the artist and to him, a scene with sheep and shepherds would not have seemed complete without the dog.

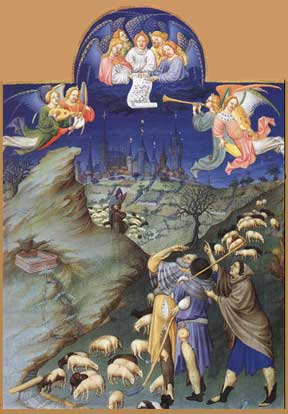

Above, center left, "The Annuciation to the Shepherds" from the Trivulizo Manuscript Book of Hours, late 15th century, by Simon Marmion (1425-1489), a French painter of illuminated manuscripts. Currently residing in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, the National Library of the Netherlands. Beside it is a detail showing the shepherd's dog. Above, center right, "The Annunciation to the Shepherds" from the Book of Hours for the Diocese of Avranches use, ca. 1480, and currently residing in the Avranches, Normandy, Museum. Beside it is a detail showing the shepherd's dog.

Books of Hours

ca. 1300-1600

Right, "Annunciation" by "the Bedford Master", from a book of hours, ca. 1430-1445, meant for use in Rome and Paris; and the detail showing the dog.

Right, "Annunciation" by "the Bedford Master", from a book of hours, ca. 1430-1445, meant for use in Rome and Paris; and the detail showing the dog.

A book of hours is the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Each book of hours is unique in one way or another, but all contain a collection of texts, prayers and psalms, along with appropriate illustrations, to form a reference for Catholic Christian worship and devotion...Books of hours were usually written in Latin, although there are some examples entirely or partially written in vernacular European languages. Several hundred thousand books of hours have survived to the present day, scattered across libraries and private collections throughout the world.

Originally the prayers in a book of hours were private ones but by the 12th century they had become routine liturgical ones in the monasteries. After...1215, laymen also become interested in them...By the 15th century, various stationer's shops mass-produced books of hours in the Netherlands and France. In the late Middle Ages, books of hours often started with a timetable indicating religious holidays. (From Wikipedia)

Far left, "Annunciation to the Shepherds" by the "Master of the Geneva Latini Hours" ca. 1470, for use in Rouen, France. Like the previous one, above, this one is attributed to an unknown "Master". Left, the detail showing the dog

Far left, "Annunciation to the Shepherds" by the "Master of the Geneva Latini Hours" ca. 1470, for use in Rouen, France. Like the previous one, above, this one is attributed to an unknown "Master". Left, the detail showing the dog

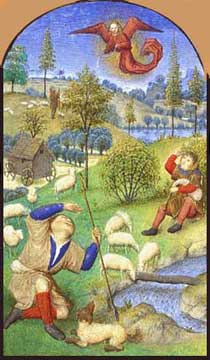

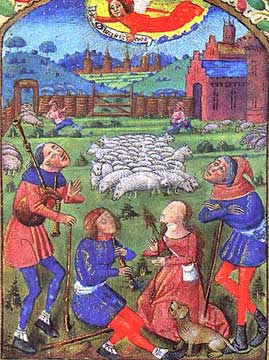

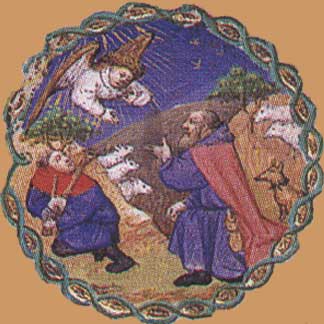

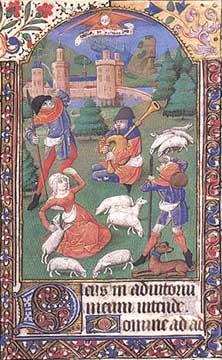

Like the Holkham Bible, below, books of hours were often made for or donated to various parishes as vehicles for teaching. The pages pictured here come from Rome, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and England. They all illustrate the Annunciation to the Shepherds and were chosen because they had shepherds' dogs in them. As you can see, the dogs do not look anything like the collies we are used to thinking of as shepherd's dogs. This could be for a number of reasons. Some of the illustrators were respected artists of the day, but others were monks or lay-persons without much skill at drawing or painting. They may not have seen shepherds' dogs, or their lack of skill just didn't allow for accurate representation. Or perhaps the dogs used then were whatever they had to hand. Some of the dogs look like hounds, others look almost like sheep, some look like small terriers. It was the style to portray the important characters in a story (like the shepherds and angels) large and everything else small in comparison. The sheep often fell into this latter category, and likely the dogs did too. However, the fact that so many of them do have dogs in them at all indicates that dogs were associated with shepherds, just as sheep were, and the presence of dogs was as necessary to identify these men and women as shepherds as the presence of sheep.

Above, four illustrations of the Annunciation to the Shepherds from books of hours residing in the Hague (the Netherlands), and below, the details showing the dogs from each of them. They are, left to right: Book of Hours for use of Paris, France, made for Fransoise Brinnon by her husband Jehan de Luc, Lord of Fontenay and Marilly, ca. 1524; Book of Hours and Prayer Book, made in Southern Netherlands ca. 1490-1500, with an added section and miniatures ca. 1500-1525; Book of Hours of Catherine de Medici, for use of Rome, made in France ca. 1560; and Book of Hours for use of Rome and Saurm/Rouen, made in Central France (possibly Le Mans) ca. 1485-1500.

This black and white illustration, far right, of the Annunciation is from the same era as the others, but its origin is not known. There is a tiny dog with the figure in the bottom, right, as the detail shows.

This black and white illustration, far right, of the Annunciation is from the same era as the others, but its origin is not known. There is a tiny dog with the figure in the bottom, right, as the detail shows.

Left, a really nice illustration of the Annunciation from a French Book of Hours, Tres Riches Heures, which has a tiny black and white dog in the bottom, center.

![]()

We have others illustrations from books of hours which we may put up at another time if we have space. We wish to thank Aaron Garceau for his excellent website on Bagpipe Iconography and for his kind permission to reprint some of his images. It just so happened that, besides bagpipes (which you can see in the pictures of this section) they also had shepherds' dogs.

We have others illustrations from books of hours which we may put up at another time if we have space. We wish to thank Aaron Garceau for his excellent website on Bagpipe Iconography and for his kind permission to reprint some of his images. It just so happened that, besides bagpipes (which you can see in the pictures of this section) they also had shepherds' dogs.

I wanted to put up one more picture, the one at left. It is from the De Damhouder Triptich by Pieter Pourbus (1510-1584), who was a Belgian painter from Bruges. It is the only one that we have come across that has a dog that actually looks like it could be a collie, and a black and white one at that. This is a step in the right direction.

FROM SECULAR SOURCES

Above, a portrait of Chaucer

from Cassell's History of England, 1902

Geoffrey Chaucer

1343-1400

One of the earliest mentions of what appears to be a shepherd's dog comes to us from the 14th century and Geoffrey Chaucer. Sometimes called the "father of English Literature", Chaucer actually wrote his Canterbury Tales in Middle English. In "The Nonnes Tale", the phrase "ran Colle our dogge" is uttered. Colle is often thought to be a sheepdog or collie and that the name is akin to "Blackie". It is not a proven fact.

Chaucer was born in London. There are few detail of his early life, but he seems to have written many things besides Canterbury Tales, for which he is best known. He was also a courtier, a diplomat, and a civil servant, working for kings Edward III, Richard II and Henry IV). Chaucer's life and death are a bit of a mystery, and the last mention of him is in 1400, though his exact date of death is not known. He was buried in Westminster Abbey and 150 years later his remains were moved to a more ornate tomb making him the first writer to be interred in the "Poets' Corner". (Most of the information in this paragraph was gleaned from Wikipedia.org.)

Above, a photo of a detail of a brass monument

to Sir Anthony Fitzherbert and his wife

in the chancel floor of the church at Norbury, Derbyshire, England

Sir Anthony Fitzherbert

1470-1538

Perhaps the first, and at least one of the earliest major treatises on husbandry was published in the reign of Henry VIII in 1534 by Sir Anthony Fitzherbert.

Born in Derbyshire, Fitzherbert was the sixth son of Ralph Fitzherbert and Elizabeth Marshall of Norbury. His brothers died young so he succeeded his father as lord of the estate granted to his family in 1125. He studied at Oxford, and was made "serjeant-at-law" for the king, eventually becoming a Justice of the Court of Common Pleas. He was knighted in 1516.

Fitzherbert was apparantly a real Rennaissance Man. He was, as the editor of the 1882 edition of his Book of Husbandry says, "a country gentleman, rich in horses and in timber, acquainted with the extravagant mode of life often adopted by the wealthy, and at the same time given to scholarly pursuits and to learned and devout reading." In 1514, Fitzherbert published a digest which was the first systematic attempt to provide a summary of English law. In 1519 he published an edition of the "Magna Carta with various other statutes". In 1523 he published three other works, including the Book of Husbandry and the Book of Surveying and Improvements (which is a treatise on the law and agriculture). And he continued to publish other law books throughout the rest of his life. He was a devout Catholic and opposed the king's suppression of the monasteries, but did not seem to be disadvantaged because of it.

Fitzherbert was apparantly a real Rennaissance Man. He was, as the editor of the 1882 edition of his Book of Husbandry says, "a country gentleman, rich in horses and in timber, acquainted with the extravagant mode of life often adopted by the wealthy, and at the same time given to scholarly pursuits and to learned and devout reading." In 1514, Fitzherbert published a digest which was the first systematic attempt to provide a summary of English law. In 1519 he published an edition of the "Magna Carta with various other statutes". In 1523 he published three other works, including the Book of Husbandry and the Book of Surveying and Improvements (which is a treatise on the law and agriculture). And he continued to publish other law books throughout the rest of his life. He was a devout Catholic and opposed the king's suppression of the monasteries, but did not seem to be disadvantaged because of it.

The first part of the Boke of Husbandry is given over to preparing the fields and growing crops. A good deal is then devoted to raising livestock and treating livestock diseases. For example Fitzherbert explains that if a cow dies of a disease, the owner must bury the corpse deep in the ground so that no dogs may find it, "For," he says, "as many beastes as feleth the smelle of that caryen, are lykely to be enfecte" (as many beasts as feel the smell of that carrion, are likely to be infected). It is interesting to note that so much (and yet so little) was known about disease and infection, despite the fact that it would be almost another 300 years before there was a veterinary school in England.

There are a very large number of chapters devoted to horses, being a proper husband and landowner, and to religion, but the chapters we are interested in come earlier in the book, on sheep, for the shepherd's dog is mentioned there. In the chapter "To make an ewe to loue her lambe" (love her lamb) Fitzherbert says:

If thy ewe haue mylke, and wyll not loue her lambe, put her in a narrowe place made of bordes...a yarde wyde, and put the lambe to her, and socle it, and yf the ewe smyte the lamb with her heed, bynd her heed with a heye-rope , or a corde, to the syde of the penne: and if she wyl not stande syde long all the lambe, than gyue her a lyttel hey, and tye a dogge by her, that she may se hym: and this wyll make her to loue her lambe shortely...

["If your ewe has milk, and will not love her lamb, put her in a narrow place made of bordes...a yard wide, and put the lamb to her, and suckle it, and if the ewe butts the lamb with her head, bind her head with a hay-rope, or a cord, to the side of the pen: and if she will not stand sideways to the lamb, then give her a little hay, and tie a dog by her, that she may see him: and this will make her love her lamb shortly..."]

Later, Fitzherbert says:

...And a shepeherde shoulde not go without his dogge, his shepe-hoke, a payre of sheres, and his terre-boxe, eyther with hym, or redye at his shepe-folde, and he muste teche his dogge to barke whan he wolde haue him, to ronne whan he wold haue hym, and to leue ronning whan he wolde haue hym; or els he is not a cunninge shepeherde. The dogge must lerne it, whan he is a whelpe, or els it wyl not be: for it is harde to make an olde dogge to stoupe.

[...And a shepherd should not go without his dog, his sheep-hook, a pair of shears, and his ????-box, either with him or ready at his sheepfold, and he must teach his dog to bark when he would have him (bark), to run when he would have him (run), and to leave off running when he would have him; or else he is not a cunning shepherd. The dog must learn it when he is a whelp, or else it will not happen: for it is hard to make an old dog to stop.]

Fitzherbert also has brief chapters on the "properties" of other animals, including the badger, the lion, and the fox, and, if you can believe it, the "properties of a woman"! The latter includes to be cheerful, have a broad forehead and buttox, and other traits that Fitzherbert found pleasing in horses as well! At first I thought he may have been writing tongue in cheek, but realized he was serious when I arrived (via pigs and property) at the chapter on wives.

Above, the "Chandos portrait" of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

1564-1616

Born in Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare is regarded as the greatest writer and playwright in the English Language; he certainly was one of the most prolific. There is much controversy over whether he or some other or others actually wrote his poems, sonnets, and plays, but we will not debate that here. When he was 18, Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, and they had three children. Between 1585 and 1592 he moved to London and began a successful career as an actor and writer. In 1613 he retired to Stratford-upon-Avon, where he died three yeas later. (Some material in this paragraph gleaned from Wikipedia.)

Shakespeare was, more or less, a contemporarty of Caius (he was actually his junior by a half century), and it is said that he based his eccentric Dr. Caius in The Merry Wives of Windsor on Johannes Caius. Dogs are mentioned frequently in Shakespeare but usually in the context of a curse (for example, in Richard III, Act I Scene II, Gloucester calls a Gentleman an "unmanner'd dog!"). However, in King Lear (written between 1603 and 1606), a "bobtail tike" is mentioned. This is a term often used to describe the bobtail or Old English Sheepdog.

Copyright 2014 by Carole L. Presberg

THE OTHER WEB PAGES WE MAINTAIN

These web pages are copyright ©2014

and maintained by webmeistress Carole Presberg

with technical help from webwizard David Presberg

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

If you are interested in using ANY material on this website, you MUST first ask for permission.

You may email us at carole@woolgather.org.