![]()

BORDER COLLIE COUSINS

THE HERDING DOGS OF NORTH AND SOUTH AMERICA

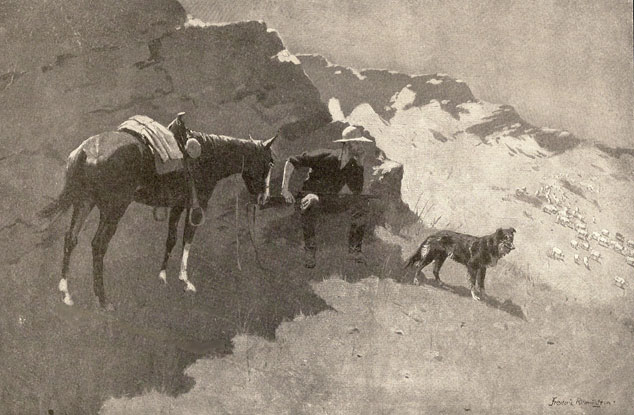

Above, drawing of a sheepherder resting on the side of a hill, with his sheepdog and horse

from Done in the Open, Drawings by Frederic Remington,

with introduction and verses by Owen Wister and others,

©1902 by P.F. Collier and Son, Publishers

INTRODUCTION TO THE HERDING DOGS OF NORTH AND SOUTH AMERICA

In order to understand the herding dogs of North and South America, we also need to understand the early history of these two continents and the development of the livestock industry, in particular, the sheep industry. Without going too deeply into American History, which is complex and sometimes confusing, what we need to know is just how American History affected the sheep industry, and as a result, the shepherd's dog in the Americas.

The Spanish Southwest

Right, detail of "Las Meninas" by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660), shows some of the royal family of King Philip of Spain, with a Spanish Mastiff in the foreground. (Photo from Wikipedia, in the public domain.)

Right, detail of "Las Meninas" by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660), shows some of the royal family of King Philip of Spain, with a Spanish Mastiff in the foreground. (Photo from Wikipedia, in the public domain.)

Edward Norris Wentworth, writing in America's Sheep Trails (Iowa State College Press, 1948), eloquently introduces us to the beginning of the sheep industry in the Americas:

"Concealed and nearly obliterated beneath the dust of migratory ovine hooves, the paths and highways of the conquistador and his Hispanic soldiery have laid buried for over four centuries. Not only did the wether and yeld ewe (provided for the meat ration) travel with the trains of the Spanish armies--grazing the herbage of each day's march and bedding down near each night's bivouac--but breeding flocks accompanied settlers into the new provinces and established themselves in unfamiliar environments...Streams that ultimately became channels of commerce watered ewes and lambs along their barren banks.

"Christopher Columbus['s] fleet set sail from Spain on September 24, [1493 on his second voyage to the New World.]...The crew hauled overside an unspecified number of sheep, goats, cattle, and calves, as well as eight hogs, with which to stock the new colonies... By November 3 it sighted Española (modern Santo Domingo), where a small colony was established with a few sheep and cattle to serve as breeding nuclei. Weighing anchor again, the ships reached the harbor of Isabella in the Island of Cuba about mid-Decemer, where was founded the first [Spanish] city of the New World....

"Spanish records as to the actual number of livestock in each expedition to the New World are rare...the chance of [livestock] survival [after Indians freed] livestock to breed under ferel conditions...was usually greater than the chance of flocks and herds [surviving the voyage] from Spain....

"As ranches became occupied and prosperous [in the islands] it proved increasingly difficult for new emigrants from Spain to secure locations. Word of lands to the west had been obtained from the Indians, and expeditions to those shores were soon planned...Hernando Cortés...[was selected to lead an expedition to Mexico...a rebel, he burned his ships on the Mexican coast and committed his future to that country. When the Aztec rule crumbled before him in 1519-21, Cortés sent back to San Domingo for more sheep and cattle, and he imported large numbers of Merino [sheep] during the next decade...As far as the eye could reach, his flocks and herds grazed."

Thereafter, Mexico, New Mexico, Texas, and Florida fell into the hands of the Spanish, and later, Louisiana and California. Wentworth calls these acquisitions colonization by sheep. Horses, cattle, and particularly sheep, were extremely significant to the development of the entire Southwest. The Spanish built missions wherever they went, ostensibly to convert the Indians, but also to control the settlements that grew up around them. Sheep fit well into these missionary programs, supplying food, and wool for clothing, and the labor provided by converted Indians (some of them slaves) could be supervised easily by a priest with the help of one or two soldiers.

Again, Wentworth's evocative words describe the Old Spanish Trail: "Communications between the Spanish Colonies farther east and California opened up a trail (eventually between Santa Fe and Los Angeles) that bore the hoofprints of thousands of sheep in later years." By the end of the 18th century, these trails had provided Spanish sheep to much of Texas and New Mexico, and eastern Arizona to California.

Left, a modern Spanish Mastiff. (Photo from Wikimedia Commons by dobroide and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license, or 2.5 Generic license, or 3.0 Unported license.)

Left, a modern Spanish Mastiff. (Photo from Wikimedia Commons by dobroide and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license, or 2.5 Generic license, or 3.0 Unported license.)

It is unclear if the Spanish had herding dogs, for there is no mention of any in texts on the Spanish conquest of the New World. It is very likely that they had livestock guardian dogs. Ogden Tanner (The Ranchers, Time Life Books, 1977) says: "The earliest Mexican sheep dogs were primarily guards rather than herders, large, ferocious creatures of uncertain lineage trained to protect the sheep against all attackers..." and Wentworth says "This sheepdog of Spain was a tramendous animal--more than 30 inches tall at the shoulder...These dogs were devoted to their masters and flocks, but showed extreme ferocity against intruders." They were in all liklihood Mastiffs, ancestors of the Spanish and Pyrenean Mastiffs of today who can be described in those very words. During the Middle Ages, the Spanish Royal Council of the Mesta was a powerful association of sheep owners in the medieval Kingdom of Castile that controlled the great flocks of sheep that were driven from the pastures of Extremadura (in the central plains) to Castile (in the northern mountains) and back again according to season (a process called "transhumance"). Dogs were not used for this purpose, and were in fact prohibited, except for livestock guardian breeds. These were the sheep, and most probably these were the dogs, that arrived with the Spanish conquistadors and colonists, and were refreshed from time to time with more importations from Spain. Those that came to the Americas, Wentworth says, "intermixed rather freely with the half-wild curs belonging to the Indians," and yet remained useful in their original capacity.

Dogs of this nature were needed, as the New World was populated by wolves, coyotes, bears, mountain lions, bobcats, lynx, eagles, and stray dogs, all of which were known to prey on defenseless sheep. In defense of the bear, one must say "their carnivorous reputation not withstanding, most bears have adopted diets of more plant than animal matter and are completely opportunistic omnivores" (Wikipedia). Still, when presented with such abundant meat on the hoof, some bears will take prey as large as a sheep, and can easily steal a carcass from other large carnivores. Winifred Kupper says, "The Spanish dog or Mexican cur, as he was often called, had to learn how to drive sheep, too in a manner suited to moving them over long distances." (The Golden Hoof, The Story of the Sheep of the Southwest, Alfred A. Knopf, 1945.)

The British Colonies

Sheep were brought into the eastern British colonies early on, but due to various reasons most did not survive. By 1650 there were only three thousand sheep in the Jamestown Colony. The Duch were more successful in importing livestock, but because of the monopoly that weavers in Amsterdam held, no woolen fabrics were allowed to be produced by the colonists. In the various settlements around New England, colonists were able to keep sheep on the commons, so, while flocks remained small because pastorage was limited, this encouraged the raising of sheep. Wentworth says that "In 1656 the Massachusetts General Court ordered all commons cleared for sheep." Losses due to wolf predation prompted a system of "night folding". Sheep were used for fertilizing cropland by using a system of moveable hurdles. The English, like the Dutch, attempted to reserve the right of textile production in the Homeland, but the English were less effective at it than the Dutch were, and woolen fabric was produced in colonial households.

There were sheepdogs in the original states. Wentworth tells of Henry More, who, just before the Civil War "was running sheep on twenty-five acres in Webster County, Virginia, and had sent to Switzerland for two sheep dogs in 1860." Switzerland? Were these herding dogs or livestock guardians? We may never know. He also says that:

"In the eastern colonies, 'shepherd' dogs were descended from British stock. Most of them were rough-coated dogs of rather general breeding. In England, this kind of dog was known as the 'drover's or butcher's dog' as distinct from the 'colley' and was a strong-framed, short-tailed animal of superier intelligence. In color the strain was black and white, blue or gray, white, fawn, or brindle and white, and occasionally solid colored. While these dogs were used principally for cattle, they were readily trained for sheep...Apparantly the modern breed known as the 'Old English Sheep Dog' was related to this stock--though selected toward a different ideal recently.

"The 'Scotch collie was imported freely by the middle of the [19th] century. This dog was not the so-called 'show type' of collie but was smaller-framed, broader-headed, and quicker in action. Collies spread rapidly in the northern states, especially in New York, Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin...The black and white, and sable and white varieties were the more popular..."

There was droving all over the Eastern United States along all the major river valleys starting in 1790s. Cattle (and likely sheep) were raised in the hill districts of the Connecticut valley and then driven to the Boston stockyards. Livestock from the Pennsylvania back country as well as from the Carolina Piedmont and the salt marshes along the coast were driven into southeastern Pennsylvania, where farmers bought and stall-fed them to fatten them for market. Stock from New Jersey was driven to the posts still maintained by the British along the Canadian border. Cattle (and again, likely sheep) were driven through the Cumberland Gap to Kentucky. Livestock from Ohio were regularly marketed at the eastern stockyards, and some purchased in Ohio were driven to the Genesee valley (New York) for pasture fattening, and then to Fort Niagara, Philidelphia, New York City's Bull's Head market, and even Baltimore. ("Cattle Driving from the Ohio Country, 1800-1850" by Paul C. Henlein, Agricultural History, the Agricultural History Society, 1954.)

But, in 1898, William De Witt, a New York City lawyer and a drafter of the New York City Charter, addressing the Annual Meeting of the New York State Bar Association, noted that "the drovers no longer descend the gorges of the Catskill [Mountains in New York State] with their shepherd dogs, driving their flocks of sheep and herds of cattle to the valley [of the Hudson] river..." The day of the long distance cattle and sheep drives in the East was over. Sheep were still driven locally on a very small scale, from winter pastures in the villages and farmsteads to summer pastures in the hills. For example, Mr. Preston Davenport, an early sheepdog trialist in New England, wrote "In 1924...I bought my first Border Collie...This was the beginning of an enviable association with a shy but talented companion. I didn't know anything about training a sheep dog and she knew nothing about herding sheep. We grew together. Fortunately we were busy caring for a flock of 600 sheep. Winters were spent in the valley at Bradstreet, [Massachusetts,] but in the spring the flock was taken on foot the 20 miles to the hill pasture in Colrain. Leaving at four o'clock in the morning we would make the journey by late afternoon. This was indeed an application of "necessity [being] the mother of invention", for little by little this puppy acquired the ability so necessary in the daily chores..." ("Necessity the Mother of Invention", Northeast Border Collie Newsletter, published by Nancy Hayes, 1979.)

The Settlement of the Great Plains

After the American Revolution, westward migration began in earnest and the sheep population gradually spread west with the settlers. By 1800 sheep were well established in parts of Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Kentucky. The prairies beyond were promising, and, as Wentworth says, "[t]he traffic that streamed across the Alleghen[y Mountains] during the early decades of the nineteenth century was one of the great colonizing movements of all time both in volume of emigration and in economic and political importance...In the vanguard of the movement traveled the flocks of sheep, vital to families abandoning the comforts which a century and three-quarters had developed along the Atlantic Seaboard..."

In his book (Commerce of the Prairies of the Journal of a Santa Fe Trader During Eight Expeditions Across the Great Western Prairies and A Residence of Nearly Nine Years in Northern Mexico (phew!), J.W.Moore, 1851), Josiah Gregg writes of moving sheep across the prairie. He says:

"These itinant herds of sheep generally pass the night wherever the evening finds them, without cot or enclosure. Before nightfall the principal shepherd sallies forth in search of a suitable site for his hato, or temporary sheep-fold; and building a fire on the most convenient spot, the sheep generally draw near it of their own accord. Should they incliine to scatter, the shepherd seizes a torch and performs a circuit or two around the entire fold, by which manoeuvre, in their efforts to avoid him, the heads of the sheep are all turned inwards; and in that condition they generally remain till morning, without once attempting to stray. It is unnecessary to add that the flock is well guarded during the night by watchful and sagacious dogs against prowling wolves or other animals of prey. The well-trained shepherd's dog of this country is indeed a prodigy: two of three of them will follow a flock of sheep for a distance of several miles as orderly as a shepherd, and drive them back to the pen again at night, without any other guidance than their own extraordinary instincts."

It is unclear if he is speaking about herding dogs or livestock guardians or both.

Once the settlers reached their destination on the prairies, however, sheep growers found that the "natural prairie grasses fell far short of requirements, and that a successful husbandry could be secured only when the sod was broken and hay and grains were produced," says Wentworth. They never learned what our ancestors from the Eurasian Steppe knew 3,000 years ago, that the steppe (which is just another term for prairie or grassland) can only provide for livestock if managed by pastoral nomadism or transhumance. This lesson was learned to some extent later when the West was settled. There were undoubtedly herding dogs with the sheep flocks, but little mention of them. There were no livestock guardian dogs, and the continuous attacks of prairie wolves made raising sheep even more difficult on the prairie.

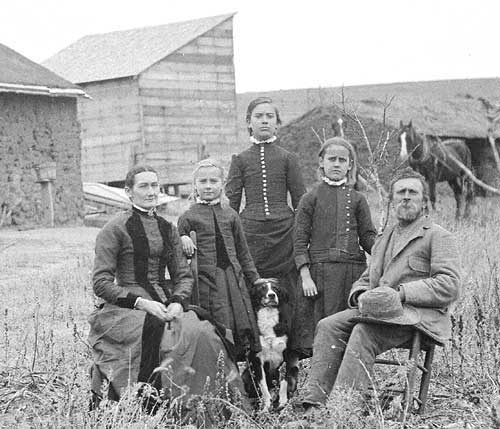

Between the years of 1886 and 1912, Nebraska photographer, Solomon Butcher, recorded the settlement of the Great Plains. He recognized that life on the plains as he saw it was transitory, and yet an important chapter in the history of the American West. Many of the photos that he took were of families, posing with their most precious possessions. Often they put on their best clothes for the session and stood or sat before their houses, which were frequently made of sod. Sometimes they had a sheepdog in the photo with them, posing as one of the family. Some had their horses brought up for the occasion, others their cows. One woman had her treadle sewing machine nearby. It's possible she actually did her sewing outside, as sod houses tended to be dark, and there was no electricity. More affluent families with wooden clapboarded houses still displayed their most loved treasures. This magnifent collection of 3500 glass plate images is in the Nebraska State Historical Society and can be viewed online. I can only present one or two here.

Between the years of 1886 and 1912, Nebraska photographer, Solomon Butcher, recorded the settlement of the Great Plains. He recognized that life on the plains as he saw it was transitory, and yet an important chapter in the history of the American West. Many of the photos that he took were of families, posing with their most precious possessions. Often they put on their best clothes for the session and stood or sat before their houses, which were frequently made of sod. Sometimes they had a sheepdog in the photo with them, posing as one of the family. Some had their horses brought up for the occasion, others their cows. One woman had her treadle sewing machine nearby. It's possible she actually did her sewing outside, as sod houses tended to be dark, and there was no electricity. More affluent families with wooden clapboarded houses still displayed their most loved treasures. This magnifent collection of 3500 glass plate images is in the Nebraska State Historical Society and can be viewed online. I can only present one or two here.

Left, a family from Nebraska pose with their sheepdog in their midst. I particularly like this one because it looks like the collie is the most important member of the family. (Photo by Solomon Butcher, courtesy of the Nebraska State Historical Society.)

The American West

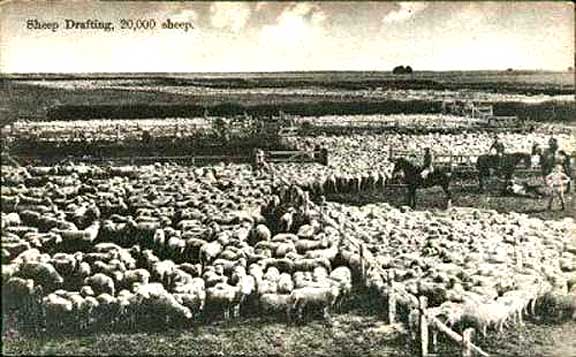

Right, sorting sheep on a Western sheep ranch. There are dogs in the photo if you look closely and the center far right.

Right, sorting sheep on a Western sheep ranch. There are dogs in the photo if you look closely and the center far right.

The West was won by a combination of ruthless conquest and courageous frontiersmanship. Mexico acheived independance from Spain in 1821. In 1848, after the Mexican-American War, Mexico ceded half it's territory to the United States, which included lower California, New Mexico, southern Arizona, and the disputed portions of Texas which had not been annexed previously by the United States. The treaty with Mexico removed all barriers to westward movement and subsequently, the Homestead Act was passed in 1862 which encouraged 600,000 families to settle in the West by giving them land. By 1870, the three Pacific states had well over three million sheep.

When gold was discovered in California in 1849, prospectors quickly depleted the local food supplies, and meat was needed to supply the gold camps. Sheep ranchers in New Mexico ran many trail drives from Santa Fe to the gold fields until the late 1850s. Accounts of the time say that it took seven mounted cowboys to move 1,000 head of cattle. The same number of sheep could be driven by a single herdsman with one good dog. The dogs used were collies. A well-trained dog on those drives did not bark, except to warn of danger, never left the flock, even to chase rabbits, and might protect the flock from predators if necessary.

Left, a sheep herder and his two collie dogs in front of the chuckwagon. (Photo from Wentworth by Beiden, undated.)

Left, a sheep herder and his two collie dogs in front of the chuckwagon. (Photo from Wentworth by Beiden, undated.)

Wentworth tells us that "the most intimate picture of the daily problems" that sheep drovers had was "presented in the diary of Dr. Thomas Flint during the drive from Illinois to California in 1853. The first task Flint faced was holding the flock on the prairie near Bloomfield, Illinois, from the back of a horse and without the aid of a dog. The acquiring of a trained sheep dog was not easy in the primitive farming communities, and the farther west one started on the trail the more difficult the purchase became."

Not everybody thought that having a sheepdog was useful. Wentworth quotes Charles Nordhoff as saying "Dogs I have found but little used in the sheep ranches I have seen. They are not often thoroughly trained and where they are neglected become a nuisance." Wentworth tells of the sheep on Santa Rosa Island thirty miles south of Santa Barbara. "In the eighties," he says, "it was owned by Alexander P. More of Boston, and the flock numbered eighty thousand head at its peak...About two hundred or more trained goats were used to control the sheep, and no sheep dogs were permitted on the island."

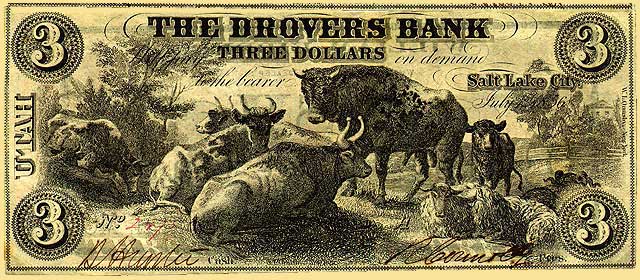

Above, a private bank note from The Drovers Bank in Salt Lake City from 1856.

Just as in Britain, drovers in America became associated with banking.

They carried large sums of money from their contractors to pay for accomodations or tolls on the way,

and were entrusted to sell the stock and bring back the cash to the flock owners.

While the generalization is simplistic, and the realities much more complicated, the results of the Lowland and Highland Clearances, the one for agriculture and the other for sheep, were that many thousands of Scots were displaced, and emigrated to the United States and Canada between 1760 and 1850, some of them forcibly. The sheep industry in Scotland began a gradual decline beginning in the 1880s, thus freeing up a large number of Scotsmen to emigrate again, though hardly on the same scale. Many Scots played an important role in the development of the American West. According to Morton Szaz (Scots in the North American West, 1790-1917, University of Oklahoma Press, 2000):

"The sheep industry in the western United States proved extraordinarily multinational, involving Navajo, Mexican, Hispanic, Norwegian, German, Canadian, and Irish herders, just to name a few. In every region of the West, however, the Scots sheepmen became prominent beyond their numbers. In some regions, such as Wyoming and Idaho, they virtually ruled the enterprise. Several Scots emigres established genuine sheep empires."

Right, a shepherd keeps watch over a flock of sheep grazing on alfalfa stubble in the Imperial Valley, Southern California. The dog is a black and white collie, but of which variety is unclear. Undated.

Right, a shepherd keeps watch over a flock of sheep grazing on alfalfa stubble in the Imperial Valley, Southern California. The dog is a black and white collie, but of which variety is unclear. Undated.

Scottish sheepmen who became successful ranchers in the American West, often employed fellow Scots to work on their ranches. One such was George Wilkins Kendall who had a ranch in Texas. In 1852, Kendall hired Scottish shepherd, Joe Tait, and also imported four "Scotch collies whose progeny were extremely helpful throughout his sheep operations..." says Wentworth.

While we don't have room for a discussion of all the Scots that became "sheep czars", one in particular is important in the history of the shepherd's dog in America. This was Andy Little, who emigrated from Moffat, Scotland in 1894, bringing with him his two sheepdogs, Katie and Jim. Little arrived in Caldwell, Idaho, where he began to work for a fellow Scot who had previously "made it". Little's story is not unusual. He took his salary in stock and soon had a small flock of his own. In 1901 he returned to Scotland, married, and brought his new wife back to Idaho with him. Seven of his eight brothers followed him to Idaho. Eventually Little owned upwards of 165,000 sheep and by the time of his death in 1940 he was known as the "Sheep King of Idaho".

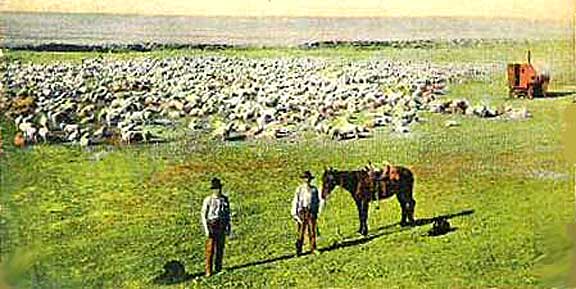

Left, a settlement camp on the sheep range, with two herders and their dogs. It is impossibly to tell just what kind of dogs these are. In the background is the sheepherders' wagon.

Left, a settlement camp on the sheep range, with two herders and their dogs. It is impossibly to tell just what kind of dogs these are. In the background is the sheepherders' wagon.

In her biograpy of Andy Little (Andy Little, Idaho Sheep King, Caxton, 1990), Louise Shadduck says, "He had arrived with the two dogs, selling one before he reached the Aikman ranch for his first job, and at the peak of his operations, he owned about a thousand dogs spread out through the various ranches and home place. Once, after visiting a number of small operations looking for sheep to buy, he said, 'You know, I've got more sheepdogs than most of those guys have sheep.' He had from one to three herding dogs for a band of a thousand sheep, with a number of additional dogs at the ranches." She quotes Little as saying that "the sheep dogs were the unacknowledged administrators of the wool industry".

Right, two of the Little herd dogs, Jim and Katie.

Right, two of the Little herd dogs, Jim and Katie.

Although Little did not believe in making pets of sheepdogs, he had his soft spots. The first pedigreed Border Collie that Little had imported from Scotland was called Old Tweed. He was black and white and lived for nearly twenty years, riding around in the car with Little. Another imported pedigreed dog was another named Jim. He also rode in the car with Little and knew nothing of herding, but Little loved him. Imported at the same time as this Jim, another Katy was a good worker. If there were any sheep missing, Katy was sent to round them up and hold them until the shepherd came, a job she could do well. Little and his workers used the names Tweed, Jim, and Katie, over and over again, making it confusing as to which dog is meant.

Some of Andy Little's dogs were blue merle, as the photo at right shows, and some of his workers preferred these "blue" dogs. One of them was Jay Sisler, who, after breaking his leg, acquired two blue merle puppies and trained them for demonstrations and trials. Linda Rorem says they were "bobtailed or docked" and became "among the most important foundation dogs of the Australian Shepherd." The term "Australian Shepherd" was known in the West for some time. Andy Little called some of his crosses "curs". It may be that, as Shadduck says, he called them curs because they were mixed breeds; "but," she says, a "cur is of unknown ancestry and Andy knew exactly [the breeding of] his dogs," even if they were mixed. However, it is possible that they were mixed when he bred pedigreed collies with collies that had been brought from Australia with loads of Merino sheep. And it is possible that he called them "curs" because they had no tails because he docked them to distinguish them from his pedigreed dogs. He was Scottish after all, and in Scotland "cur" meant "curtailed" or "docked tail", something that was done to a working dog so as not to have to pay a license fee. His pedigreed dogs were Border Collies imported from Scotland, and these he called "Scotch collies." He also ran some of his Border Collies in the sheepdog trials of the day in Idaho, and they did very well, which is why they were sought after by other sheep farmers and ranch workers.

South America

The nature of the colonization of South America with regard to sheep is difficult to acertain. It was a long process that began in the 16th century and included brutal conquest by both Portugal and Spain. Sheep were introduced into most of South America at colonization. Did the Spanish and Portugese bring livestock guardian dogs with them as they did in the American Southwest? Undoubtedly, not just to protect their livestock, but to subdue the natives. The independant countries that emerged from the colonies in the 19th century, are varied in climate and terraine.

There are over 260 species of carnivors in South America, the majority of which feed primarily on meat, but mostly on small animals. Of these, thirteen are cat species, including the cougar, which is doing well, and the jaguar, which is endangered, both cats that could easily bring down a sheep. For canids, most are foxes that do not threaten adult sheep, but the bush dog and the maned wolf, both near threatened species, could bring down a sheep. The former forms packs which are most dangerous to sheep flocks, but the latter does not. The only bear in South America is the spectacled bear, which is a shy, mostly vegetarian animal, and therefore not a threat.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries Europeans emigrated to South America, particularly to Argentina. From a book written by a German television documentary crew (Dog's Best Friend: Journey to the Roots of an Ancient Partnership by Ursula Birr, Gerald Krakauer, andd Daniela Osiander. Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont, 1996.) we learn that "They came from Wales, Scotland, and England. They crossed the Andes and came through Chile; they arrived by ship from Naples, or sometimes from...German[y], to a wild, new, and unknown coast. Landless peasants from Spain, as well as escaped Russian serfs, belonged to this incoming army of immigrants." Irish settlers arrived in Patagonia as sheep farmers and agricultural labourers in the 19th century. Beginning in 1825, Scots began to arrive. As in North America, some founded large ranches, others were shepherds looking to work on farms and ranches. They brought with them their working collies, which interbred with local working dogs (likely of Indian and/or Spanish descent). These formed the basis for the South American sheepdogs of today.

Below, "Last Day in Old England" (artist unknown) shows a group of refugees departing on a transport ship.

One of them, the man seated at the center is dressed as a shepherd and has his collie dog between his knees.

Copyright © 2014 by Carole L. Presberg

Return to

![]()

BORDER COLLIE COUSINS

THE OTHER WEB PAGES WE MAINTAIN

These web pages are copyright ©2014

and maintained by webmeistress Carole Presberg

with technical help from webwizard David Presberg

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

If you are interested in using ANY material on this website, you MUST first ask for permission.