![]()

THE DROVERS

Above, "The Handsome Drover" by Haywood Hardy

This Scottish drover, with his large, flat "bonnet"

--these were knitted and then

washed and blocked

or stretched over a dinner plate, which gave them their enormous size--

is on horseback and driving four "stirks" or castrated bull calves to market.

He is being assisted by a tricolored collie, as handsome as he is.

[This article first appeared in a much smaller version in the Shepherd's Dogge Magazine, Vol. X, No. 1, Spring 1997]

"Without the shepherd's dog the mountainous land of England and Scotland would not be worth sixpence.

It would require more hands to manage a flock of sheep and drive them to market

than the profits of the whole were capable of maintaining."--James Hogg

Left, "A Highland Drove", artist unknown, but we believe it could be Heywood Hardy again. Note on the far right is the drover's dog.

Left, "A Highland Drove", artist unknown, but we believe it could be Heywood Hardy again. Note on the far right is the drover's dog.

Click here for more information on Scottish Highland Cattle

Although,

James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd and poet from the Scottish Borders,

gave us a much quoted and graphic idea of the importance of British sheepdogs,

one is struck time and again by the fact that shepherds' and drovers' dogs are

barely alluded to in literature. Folksongs, poetry, novels and history abound

with pastoral references. Shepherds falling in love or the lonely life of the

shepherd are frequent themes. Histories of the sheep and wool industry in

Britain fill volumes, but the shepherd's dog, so much a part of the shepherd's

life, is hardly ever spoken of. In his landmark book, The Drove Roads of

Scotland (Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd., London, 1952, 1953) A.R.B. Haldane says

"Dogs were extensively used in droving,...although there is curiously little

mention of them in contemporary records..." Why is that?

One explanation is that it was not ordinarily shepherds that wrote about the pastoral life (the notable exception being James Hogg himself, and he did write liberally about his own sheepdogs); and, while to a shepherd a dog may be important, this fact might be completely overlooked by contemporary writers. "What of the drover's dogs?" asks K. J. Bonser (The Drovers, Who They Were and How They Went, An Epic of the Countryside, Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1970). "These [were] faithful and indispensable aids on the long, trying marches..." Could it be that drovers' dogs were considered merely tools--indispensable but not worth singing about? "It is not surprising we know so little," says Shirley Toulson, "for no one bothers to record the ordinary" (The Drovers by Shirley Toulson, Shire Publications Ltd., Aylesbury, 1980).

These curious facts make understanding the role of sheepdogs difficult, and writing about drovers' dogs becomes a complex task. But piece by piece, with the invaluable help of Hogg and more modern writers, and with the evidence from artists like Richard Ansdell and Edwin Landseer (whose paintings record the lives of shepherds and drovers and their dogs), an image of shepherds' and drovers' dogs emerges. Before we see what the dogs were like, we need to examine the history of droving itself and try to understand its importance in the economy of Britain, particularly in its heyday from the 17th to the 19th centuries.

In the two illustrations, above, from paintings by an unknown artist or artists, made during the droving era in Scotland, we see what might have been the differences in the dogs preferred by drovers versus dogs preferred by shepherds. The one on the left is entitled, "Drovers", and shows two men in highland dress, eating oatmeal from a wooden firkin or bowl. Their dog looks on. He is a small, smooth-coated collie. The one on the right is entitled "Highland Shepherd" and depicts a man in highland dress carrying a crook, accompanied by a rough-coated collie.

PART I: DROVING IN BRITAIN

Wild cattle (aurochs) were a part of the native fauna of the forests, grasslands and marshes of post-glacial Scotland...and, when the ice retreated, it became a resident species; its remains have been found northwards to Caithness...When Neolithic and Bronze Age people colonised Scotland, domestic (Celtic shorthorn) cattle arrived with the[m]...about 5000 years ago...The wild and domesticated cattle may have existed together in places until the ninth or tenth century when the aurochs became extinct in Scotland...The original domesticated Celtic shorthorn became the Kyloe, the cow of the Highlands and Western Isles--the breed stock of Highland cattle [today],...Small, hardy black cattle, they were described by Bishop Leslie in 1578 as 'not tame...like wild harts (deer)...which through certain wildness of nature, flee the company or sight of men.'" (From "The Economics and Ecology of Extensively Reared Highland Cattle in the Scottish LFAs: an example of a self-sustaining livestock system", Davy McCracken, et al, Scottish Agricultural College, Ayr.)

Above, "Going to Market" by Richard Ansdell. Here we see alarge flock of sheep being driven to market. There are at least two drovers with the flock, and although we only see one dog (a collie) there are probably several more.

When the population of an area was small and isolated, most of the land could be used for grazing, and some for the growing of crops. But as populations increased, pressure on the land increased as well, and use had to be made of the poorer, higher land for grazing.This often entailed the seasonal relocation of whole or partial communities along with their livestock--transhumance. During late autumn and winter the pastoral community occupied homesteads on the edge of the valleys or on the coastal lowlands. During late spring and summer they would remove their stock to the higher mountain pastures, thus allowing the better land to be used for hay and other crops. In the high pastures part of the community would live in temporary dwellings while the rest would tend the fields below. "Transhumance," McCracken et al say, "still prevailed on low-lying land in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and probably continued to operate on moors, marshes and seasonally flooded land until late medieval times; in the Hebrides, low-lying shielings existed until recent times, but generally by the seventeenth century the substantial areas of grazing [used] for [local] transhumance were on the hills and mountains...The earliest surviving written documents referring to transhumance date from the twelfth century..." (ibid.)

"We do not know exactly when droving began," says Bonser, "but we do know that the early inhabitants of Britain moved large herds of cattle and sheep, raiding, or in search of fresh pasture." Transhumance means "the transfer of livestock from one grazing ground to another, as from lowlands to highlands, with the changing of seasons (The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, 2000). "Droving, on the other hand, means "To drive, as cattle or sheep, especially on long journeys; to follow the occupation of a drover" (Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary, 1996). The difference might seem subtle, but as soon as people began moving livestock for the purpose of trade or business, droving as a profession was born.

As the populations of the cities grew, there became a great demand for wool for clothing, beef as food, and skins and hides for shoes, boots, and many other items. With that demand, the number of sheep and cattle raised in the less populated areas and then driven to market, also inclined. The easiest way to transport meat, skins and hides is on the hoof--driving the animals to markets and abattoirs closer to the populated areas. "The total number of cattle in Scotland in early times is not known," says McCracken et al, "but the Exchequer Rolls for 1378 show the number of hides exported as being nearly 45,000. In the early sixteenth century [it was] reported that many men possessed as many as 10,000 sheep and 1000 cattle. During the thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries cattle were the main form of transportable wealth. By the end of the sixteenth century the beginnings of a well organised trade in cattle began which involved the movement of large numbers annually from the distant pastures to the main markets in central Scotland and from there to England. This trade in cattle persisted into the nineteenth century. In 1777, 90,000 head were sold in Falkirk and by 1850 this had risen to 150,000 per annum." (loc. cit.)

As the populations of the cities grew, there became a great demand for wool for clothing, beef as food, and skins and hides for shoes, boots, and many other items. With that demand, the number of sheep and cattle raised in the less populated areas and then driven to market, also inclined. The easiest way to transport meat, skins and hides is on the hoof--driving the animals to markets and abattoirs closer to the populated areas. "The total number of cattle in Scotland in early times is not known," says McCracken et al, "but the Exchequer Rolls for 1378 show the number of hides exported as being nearly 45,000. In the early sixteenth century [it was] reported that many men possessed as many as 10,000 sheep and 1000 cattle. During the thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries cattle were the main form of transportable wealth. By the end of the sixteenth century the beginnings of a well organised trade in cattle began which involved the movement of large numbers annually from the distant pastures to the main markets in central Scotland and from there to England. This trade in cattle persisted into the nineteenth century. In 1777, 90,000 head were sold in Falkirk and by 1850 this had risen to 150,000 per annum." (loc. cit.)

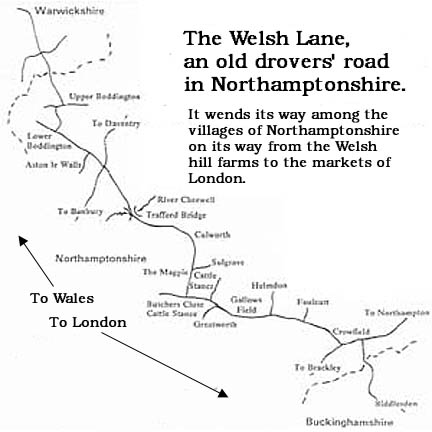

Droving took place all over Britain, and there were large cattle and sheep markets in Scotland, England, Ireland and Wales. Bonser points out that the earliest drove roads in Britain were followed by Neolithic man, and some of them, he says, are 6,000 years old. Droving is a very old profession, attested to by numerous clues. Settlements grew up around drovers' meeting places and towns and inns along their route flourished from the business. The city of Oxford in England, for example, is believed to have first been established by Saxon ox-drovers fording the river (at the ox ford) near Christchurch meadow. (OXTowns Ltd., 1995-2005).

There is a lane at St Michael, in Cold Kirby, Yorkshire, running north-south along the western edge of the parish, which was once part of the ridgeway or drove road. For centuries the road was a major thoroughfare for Scots drovers, bringing Galloway and West Highland cattle down to the Malton and York markets. In the mid-18th century, over 30,000 head of cattle were driven over this road each year.

Above (in white), an old drover's road in Wales.

Dalwhinnie, a Scottish town that sits on one of the sources of the river Spey, in Gaelic means "meeting place", and indeed it was a meeting place for cattle drovers on their way south to market. In Ireland there is Teanga Brideig, a tongue of land jutting into the Stream of St. Bride, situated on an old droving road where the drovers traditionally asked St. Bride or Bridget for protection and blessing for their cattle. (H. McSkimming, Dalriada Magazine, 1993, Dalriada Celtic Heritage Trust).

Left, The Sma' Glen by watercolorist Alfred de Breanski.

Left, The Sma' Glen by watercolorist Alfred de Breanski.

Tomintoul, at around 1165 feet, is reputed to be the highest village in the Highlands of Scotland. It is situated at the junction of several old droving roads across the Cairngorm Hills.

Amulree, very close to the geographical centre of Scotland, was one of the oldest cattle trysts (markets or meeting places) in the country. Each year it came alive to the lowing of thousands of black Highland cattle, the barking of herding dogs and the Gaelic curses of drovers as they marshalled their huge herds ready for the sales. When the Crieff Tryst replaced the tryst at Amulree, the cattle would still be driven down through the Sma' Glen, which runs from Amulree towards Crieff and at times up to 30,000 head were grazed in the fields around Crieff. Herds were brought in from as far afield as the Western Isles, travelling about 12 miles a day.

In the Evening News (a newspaper from Edinburgh, Scotland), January 31, 1987, journalist Malcolm Archibald envisioned what it would be like for a drove to come through a farming community, in "The Invasion of the Wild Bunch":

In the central part of the Penlands there is a nick between two hills...[which] is the highest point of the Cauldstaneslap path, the Slap itself. Although the hills have change their names within the written memory of man, the path has not; Cauldstaneslap it has always been...[and] the Slap had one primary function: it was the route of the cattle drovers.

Gathered from scores of markets all over the Highlands, the hardy black cattle were driven southward toward the great trysts of the Lowlands. Highland glens echoed to the pounding thunder of hooves, the barking of drover' dogs, the rattle of the broadsword and pistol. For the drover travelled armed in the early days...Down to Crieff or, later, Falkirk, where the southern buyers gathered to select their bargains...

Picture the scene: Late in an autumn afternoon. Long shadows around the farm...and snow whitening the bleak path up to the hills. Ice clinking musically at the edge of the loch. A dozen men frantically wielding scythes to cut the meadow hay before the advent of the drove....There would be a tremble on the ground, a rumble from hundreds of hooves and one man would point, another curse.

A seemingly disorganised mob, shaggy bodies and wickedly curving horns, lumbering over the low ground. The "Gudeman"...would advance to greet the topsman...of the cattle, to implore him not to let his beasts stray onto such hay as was uncut, but the drovers would ignore him. There would be rough laughter, the lowing of cattle and sharp barks of the dogs until the topsman was settled in the farm and the drovers outside with their charges.

First to be fed would be the dogs, then the breeze would carry the smell of onions and porridge, perhaps the sweetness of horn-carried whisky, and the lilt of Gaelic would mingle with the whispering grass and song of the wind. One of the drovers might dip his long, brown and white chequered plaid in the Water of Leith, let the water freeze to ice and use the igloo effect as shelter...With only their plaids and a broad blue bonnet to protect them against the weather, the drovers were a tough bunch...With the dawn--or before--the drove would be moving again...They would leave manure behind them as the only payment...

.jpg) The picture at the left shows drovers at a fair in Cornwall in 1893, by Frank Dadd (1851-1929), with their smooth-coated collies. time.

The picture at the left shows drovers at a fair in Cornwall in 1893, by Frank Dadd (1851-1929), with their smooth-coated collies. time.

During the 13th and 14th centuries fairs proliferated throughout Britain as more Bishops, Barons and Lords were granted the right to hold weekly markets and annual fairs, many associated with specific Saints and usually linked with the rural calendar. Drovers brought their cattle and sheep to sell at these fairs.

Numerous inns in Great Britain were associated with drovers, and, although many have disappeared, some exist today that are still called by names descriptive of that association, like "The Drovers Arms" or simply "The Drover", and there are myriad others that don't show their origins as easily, but are known to have been drovers stopping places. The one above, right, is the Bottle and Glass on Binfield Heath, Oxfordshire, England. It appears to be a Tudor-style structure with a thatched roof, parts of it dating to the 14th century. The name of the pub is derived from the old drovers reference to stopping for a 'bottle and glass' of ale or whisky on their journey to Oxford.

Above, "The Thirsty Drover" by Francis William Edmonds, 1856.

Right, a "typical" type of drover's inn.

Right, a "typical" type of drover's inn.

The following examples of inn's are taken from tourist literature today:

The Drovers Arms, Howey, Wales, is a stylish red brick, Victorian building on an original Drovers route used by the Welsh Drovers to walk their cattle, sheep, pigs and geese to the rich men's markets in England since Norman times.

The Amulree Hotel [at the head of the Sma' Glen, mentioned above]--This oasis of the moors has been a haven for travellers since it started life in 1714 as a drovers' inn.

The Black Swan Inn overlooks rolling meadows and woodland and was built in the 1700s to serve the cattle drovers on their way from the North Yorkshire moors to the Vale of York, ...a broad plain lying between the fells of the Yorkshire Dales to the west and the hills of the North York Moors to the east.

Tormaukin Hotel, Glendevon, Scotland, surrounded by the Ochil Hills, [was an] 18th-century former drovers' inn.

Aultguish (Allt Giubhais in Gaelic) means the stream of the pine forest as this whole area was once covered with pine. [It lies between Ullapool on the West Coast of Scotland, and Inverness on the East Coast.] In past centuries, the Aultguish Inn was renowned as an overnight stop for drovers taking the black cattle to the markets of Dingwall or Muir of Ord.

The Bellachroy is an early 17th century droving inn [at Dervaig, Isle of Mull]. Dating from 1608, it is said to be the longest continuously inhabited building on the island of Mull. Until the late 1960s the inn was also a working farm and the buildings were converted at this time into a hotel.

"Crianlarich and Tyndrum [in west central Scotland] were established as resting and grazing places during the 17th, 18th and 19th Century cattle droving era. An inn came into existence at Tyndrum, where two drove roads met.

From the Bridge of Orchy [in west central Scotland] one crosses the wild Rannoch Moor to the Kingshouse Hotel another old droving inn.

Loch Duich Hotel in the village of Ardelve [in the North-west Highlands] is situated at the point where three sea lochs meet and overlooking the famous Eilean Donan Castle. The hotel was built as a cattle droving inn some 300 years ago.

In the early 18th century, business in [Dunblane] improved with more demand for livestock arising from an expanding cattle droving trade and from supplying the increasingly prosperous cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Above, Cut Hill in North Dartmoor. It is one of the most isolated places on Dartmoor.

It is largely surrounded by wet and tussocky ground. The high fen is not far away.

The word "cut" derives from the old drovers track, seen above, Cut Lane or Drift Lane,

which cuts through the fen that separates the Dart and Tavy river valleys

and thus allowed a more easy passage of livestock across the moor.

Left, a boy and his dog driving cattle on the road to Portree, Isle of Skye, sometime in the first half of the 20th century.

Left, a boy and his dog driving cattle on the road to Portree, Isle of Skye, sometime in the first half of the 20th century.

We have seen that the routes taken by droves were often existing ancient trancks, and Bonser says they "owe their continued preservation to successive generations of drovers." These tracks were known as "greenways", "drove ways", "drove roads", "cutways", "ox roads" and "drift ways". They often led across the higher ground of the open hills and fellsides where free grazing was readily available for the herds and where the longer views helped the leaders or

'Topsmen' to navigate and avoid ambush from theives that still plied the countryside. When turnpike roads were built it became expensive and slow to move large numbers of animals through tollgates, but the 'roads' over the hills remained free. And these tracks caused less wear on the feet of the livestock than the hard roads of the later years. Progress across country was at a slow but steady walking pace, with regular stops for rest and for grazing so that the stock did not lose weight on the journey and were in good shape when

they reached the sales.

When the drove was on their slow march over the hills the local farmers were given plenty of warning that they were coming. There would be the usual din of herded animals and barking dogs, but the drovers would also call and shout loudly when they approached farms or grazing livestock to warn the owners to get their animals safely out of the way. If the local farm animals got caught up in the mass of the drove it could be very difficult to separate them out again.

Drovers' food was meagre, oatmeal being the staple. En route, cattle were frequently bled into a bowl of oatmeal, mixed and cooked over a camp fire. This sparce meal was similar to black pudding that is still eaten today in Scotland. Drovers also carried onions, and sometimes caught rabbits to add to the pot. For most of the route, drovers slept out with their charges, but, because the journeys often took several weeks, inns like the ones mentioned above, grew up along the way to serve the drovers. These were also associated with grazing places for which the inns exacted a fee. Halfpenny House just outside Kirkby Stephen was named for the halfpenny reputedly being the charge per animal per night for grazing on the stances provided.

Once the drove reached towns and villages, the tracks often gave way to toll roads. Tolls were exacted for road maintenance, but also just for passage through certain areas, for instance, church parishes or the land that was the domain of a particular person or group. It was no wonder that drovers avoided these places when possible and kept to the more isolated and higher tracks.

Above, "Crossing The Moor" by Richard Ansdell

Sir Walter Scott, in his "short story" The Two Drovers (Macmillan, 1901) gives a vivid description of a drove from the Highlands of Scotland:

It was the day after Doune Fair when my story commences. It had been a brisk market, several dealers had attended from the northern and midland counties in England, and English money had flown so merrily about as to gladden the hearts of the Highland farmers. Many large droves were about to set off for England, under the protection of their owners, or of the topsmen whom they employed in the tedious, laborious, and responsible office of driving the cattle for many hundred miles, from the market where they had been purchased, to the fields or farm-yards where they were to be fattened for the shambles.

The Highlanders in particular are masters of this difficult trade of driving, which seems to suit them as well as the trade of war. It affords exercise for all their habits of patient endurance and active exertion. They are required to know perfectly the drove-roads, which lie over the wildest tracts of the country, and to avoid as much as possible the highways, which distress the feet of the bullocks, and the turnpikes, which annoy the spirit of the drover; whereas on the broad green or grey track, which leads across the pathless moor, the herd not only move at ease and without taxation, but, if they mind their business, may pick up a mouthful of food by the way.

At night, the drovers usually sleep along with their cattle, let the weather be what it will; and many of these hardy men do not once rest under a roof during a journey on foot from Lochaber to Lincolnshire. They are paid very highly, for the trust reposed is of the last importance, as it depends on their prudence, vigilance and honesty, whether the cattle reach the final market in good order, and afford a profit to the grazier. But as they maintain themselves at their own expense, they are especially economical in that particular. At the period we speak of, a Highland drover was victualled for his long and toilsome journey with a few handfuls of oatmeal and two or three onions, renewed from time to time, and a ram's horn filled with whisky, which he used regularly, but sparingly, every night and morning. His dirk, or 'skene-dhu', (i.e., black-knife,) so worn as to be concealed beneath the arm, or by the folds of the plaid, was his only weapon, excepting the cudgel with which he directed the movements of the cattle.

As well as cattle and sheep, geese, turkeys, pigs and donkeys were also driven to and from the fairs and markets. One way to keep them fit was to keep them shod. "The Welsh Black cattle were fitted with curved iron shoes like small horseshoes cut in half, with sections either side of the cloven hoof. These special shoes, called 'cues', sometimes had to be replaced on the long journey over very rough ground, and a blacksmith would often travel with the drovers. The pigs in the procession had little woollen boots with leather soles fitted to each trotter...Even the geese had protection for their feet. This was done by driving them through a mixture of soft tar and sand, which would form a very hard-wearing coating when it set. "

Above, "the Ferry-Boat" by Otto Weber, shows two collies (lower left), a black-and-white and a red-and-white,

herding Highland cattle onto a ramp where a drover waits with them for the ferry

(seen at the far right already loaded with cattleand crossing a loch, river, or kyle).

Roads in the heyday of droving cannot be compaired to even the smallest of country roads today. There was no drainage and during rainstorms travel could be treacherous. At some river crossings there were bridges, but they were infrequent and frequently allowed to fall into disrepair. Ones that were functional might have a toll associated with them, so that the drovers avoided them. At some crossings there might be a ferryboat, but again, a fee was required so often the drovers crossed on the ferry themselves, but drove their cattle into the water to swim across.

Above, "Welsh Drovrs Crossing the Wye" by Baxter,

a much calmer crossing than the one described below.

They are urged in a body by loud shoutings and blows into the water, and as they swim well and fast, usually make their way for the opposite shore: the whole troop proceeds pretty regularly till it arrives within about a hundred and fifty yards of the landing place, when meeting with a very rapid current formed by the tide, eddying, and rushing with great violence between the rocks that encroach far into the channel, the herd is thrown into the utmost confusion. Some of the boldest and strongest push directly across, and presently reach the land, the more timorous immediately turn around, and endeavour to gain the place from which they set off; but the greater part, borne down by the force of the stream, are carried towards Beaumaris bay, and frequently float to a great distance before they are able to reach the Caernarvonshire shore. To prevent accidents a number of boats well manned attend, who row after the stragglers to force them to join the main body; and if they are very obstinate, the boatmen throw ropes about their horns, and fairly tow them to the shore, which resounds with the loud bellowings of those that are landed, and are shaking their wet sides. Not withstanding the great number of a cattle that annually pass the Strait, an instance seldom, if ever, occurs of any being lost. ("A Drove Crossing the Menai Straits" by A. Arthur Aitkin, Journal of a Tour through North Wales and part of Shropshire, 1797)

Drovers had to hire ferries (as in the painting by Otto Weber, above) or boats to ferry their cattle or sheep over water that was too wide to swim. The photo, left, shows a drover accompanying his cattle in a boat across the Kyle of Localsh from Skye, probably early to mid 20th century. Below, cattle being driven along a beach in the Uists, Outer Hebrides, about the same time period. In this photo, there is a dog (far right).

Drovers had to hire ferries (as in the painting by Otto Weber, above) or boats to ferry their cattle or sheep over water that was too wide to swim. The photo, left, shows a drover accompanying his cattle in a boat across the Kyle of Localsh from Skye, probably early to mid 20th century. Below, cattle being driven along a beach in the Uists, Outer Hebrides, about the same time period. In this photo, there is a dog (far right).

Left, a drover and his dog at Smithfield market. Note his license on his left arm.

Left, a drover and his dog at Smithfield market. Note his license on his left arm.

Language is often indicative of the origins of a particular place or profession or trade. Earlier, we saw how Oxford in England and Aultglish in Scotland both gained their names from an association with droving. The word "whig", which today refers to "a member or supporter of a major British political group of the 18th and early 19th centuries seeking to limit the royal authority and increase parliamentary power" or "an American favoring independence from Great Britain during the American Revolution" (Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary, 1967) is said to have been "originally applied to cattle-drovers in south-west Scotland" (David Cody, Associate Professor of English, Hartwick College, the Victorian Web). It's origins were in a Scottish Gaelic term originally used to describe cattle and horse thieves. How it became to be applied to drovers is not clear, however, it may be that the profession of droving arose in cattle reaving or rustling,which, at least in Scotland, was for many years a fact of life. Or, droving, the movement of large groups of cattle, may have simply been associated with reaving in the minds of many people. "Even among the Welsh," says Bonser, "drovers had not always the best of reputations." Drove roads were often called "thieves roads", due to the fact that many of them were used in their early days for driving plundered cattle.

Early drovers, may have been robbers or raiders, but by the time of Elizabeth I they had to be licensed. A man could only apply for a Droving Licence if he was over 30, married and a house owner. No hired servants were eligible. This meant that those men who drove cattle for the big dealers had to do so under contract. Any man driving cattle without a licence faced a fine of £5 together with a term of imprisonment for breaking the vagrancy laws. The topsmen had to be men of skill and character since on them rested the huge responsibility of conducting large numbers of animals over hundreds of miles in the most challenging of circumstances. At times they were entrusted to carry great sums of money or to collect taxes. Some were commissioned to find jobs for their employers sons and daughters. They also carried news and letters. In Scotland, drovers bought cattle outright before setting out on their droves (meaning they had to have cash ready to hand), but in Wales the drovers received the cattle on trust and paid for them after they returned from their journeys to England. Drovers often carried money between farmers and merchants, were authorized to sell livestock along their routes, and were responsible for the safe delivery of both livestock and currency. Shirley Toulson, a leading authority on ancient tracks and drove roads, claims that "for centuries, at least from the time of the Norman conquest to the establishment of the railways, the most important long-distance travellers were the drovers...."

At right is a bronze casting, one of five made for the "Drover's Bank" at Westerhailes, Edinburgh, in 1992, by Mary and Gordon Lochhead of SilverSculpture, St. Andrews, Fife.

At right is a bronze casting, one of five made for the "Drover's Bank" at Westerhailes, Edinburgh, in 1992, by Mary and Gordon Lochhead of SilverSculpture, St. Andrews, Fife.

It is thus no wonder that drovers began to be associated with banking. The Black Horse, symbol of Lloyd's Bank, could be a reminder of the ponies that Welsh drovers used, though I am told this is not actually so. However, as banks in Britain have always been able to issue their own bank notes, the notes distributed by banks most closely associated with droving carried signs of that association. The Black Ox Bank set up by David Jones of Llandovery in 1799 with its notes depicting the Welsh Black breed of cattle was one of a number of drovers' banks set up in mid-Wales. The bank note above, from the Aberystwith & Tregaron Bank, dates from 1819, and has sheep for it's emblem. Even today, there are still banks called "Drover's Bank".

Copyright © 2009 by Carole L. Presberg

Please go to:

PART II: THE DOGS

THE OTHER WEB PAGES WE MAINTAIN

These web pages are copyright ©2014

and maintained by webmeistress Carole Presberg

with technical help from webwizard David Presberg

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

If you are interested in using ANY material on this website, you MUST first ask for permission.