![]()

THE DROVERS' DOGS

"Turning the Drove" by Richard Ansdell

shows a drover in typical Highland dress,

turning a large flock of sheep with the help of

two gorgeous collies, one tricolored and the other sable.

[This article first appeared in a much smaller version in the Shepherd's Dogge Magazine, Vol. X, No. 1, Spring 1997]

PART II: THE DOGS

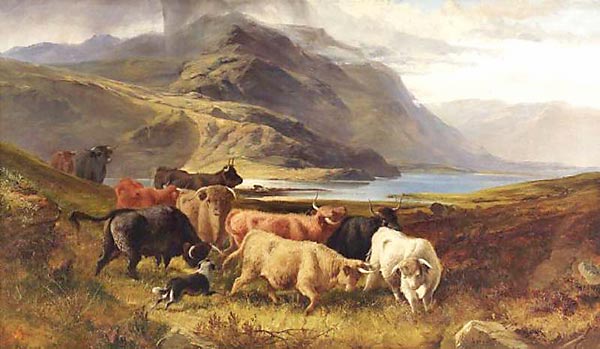

Left, a painting by Joseph Adam (1824-1895). It was labelled "Near Loch Loi in Argyllshire" but it may actually be his painting entitled "Droving in the Hills". There is as little information on Joseph Adam as there is on droving dogs. Nevertheless, this painting shows a drover driving cattle (that's him walking beside the rear-most animal) and beside him, a little to his right and slightly in front of him, you can actually see his dog, if you squint.

Left, a painting by Joseph Adam (1824-1895). It was labelled "Near Loch Loi in Argyllshire" but it may actually be his painting entitled "Droving in the Hills". There is as little information on Joseph Adam as there is on droving dogs. Nevertheless, this painting shows a drover driving cattle (that's him walking beside the rear-most animal) and beside him, a little to his right and slightly in front of him, you can actually see his dog, if you squint.

Incredibly, Scott does not mention the drovers' dogs in his story,

The Two Drovers even though he was close friends with Hogg, and his grandfather had been a drover who undoubtedly used dogs in his line of work. However, Haldane says that the "function [of dogs] must have been an important one on routes which crossed long stretches of open country." He mentions Dorothy Wordsworth's account of her ravels in Scotland: "Here," he says, "on 4 September 1803, she found the inn filled with 'seven or eight travellers probably drovers, with as many dogs, sitting in a complete circle round a large peat fire in the middle of the floor, each with a mess of porridge in a wooden vessel on his knee.' (Dorothy Wordsworth, Journals, 1798-1828.)" Hartley quotes a man named Stephens, who was 'a practical farmer', writing in an 1850 report by the Scottish Board of Agriculture. Stevens gives us one of the few contemporary accounts of what was expected of a drover's dog:

Being prepared for travel, sheep (or cattle) should have food early in the morning, and be started on their journey about midday in winter, and in the afternoon in summer. Let them walk gently away, and as the road is new to them, they will go too fast at first, to prevent which the drover should go before them, and let his dog bring up the rear...The farmer's drover may either be his own shepherd or a professional. As the flock know the shepherd, he makes the best drover, if he can be spared as long away...A drover of sheep should have his dog, not a young dog (sure to work and bark with a deal more zeal than judgment, to the irritation of the sheep) but a knowing, cautious tyke... (Lost Country Life, Pantheon Books, New York, 1979.)

Right, another of Joseph Adam's paintings, this one labelled "Droving Highland Cattle". If you look closely at both paintings, you will notice they were both painted in the same scenery, perhaps from a slightly different viewpoint. In this one, the dog can be seen clearly, and it is a Border Collie-type dog.

Right, another of Joseph Adam's paintings, this one labelled "Droving Highland Cattle". If you look closely at both paintings, you will notice they were both painted in the same scenery, perhaps from a slightly different viewpoint. In this one, the dog can be seen clearly, and it is a Border Collie-type dog.

Iris Combe also describes the dogs drovers might have had and what work was required of them:

The ancestry of these droving or bandogs, goes far back into history, and the family trees of most of our modern pastoral dogs can be traced back to those old droving types. Some of the well-established drovers perpetuated their own pure strain and there are still pockets of these strains to be found on farms today, but to distinguish the individual appearance of any of the varieties would be impossible, for they could be short, long, or half-coated and of any colour, shape or size. In their method of working some barked, some bit, others herded or hunted, and all were bred from the survival of the fittest...The skills required by drovers and their dogs were often in excess of those required by shepherds or farmers. Drovers going to local marts would work singly with one or two dogs, but for the long distance droves they formed into bands or companies...and used teams or packs of dogs trained to flank, drive, guard or hold... (Herding Dogs, Their Origins and Development in Britain, Faber & Faber, 1987.)

These dogs may have worked similarly to the way German Shepherds and other European sheep dogs are required to work. Arthur Ingham, a former inspector with the Royal Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), confirms this by telling us that "a close ally of the sheepdog was the road dog used by the drovers to herd sheep over long distances. The road dog was concerned solely with patrolling the flanks of the flock to ensure it did not stray from the ancient drove roads." (Shepherding Tools and Customs, 1977.) David Hancock also gives a vivid picture of what drovers' dogs were like. He says, in describing the bob-tailed survivors of the droving tradition still being used on the Welsh-English border, at least through the 1980s:

Unlike the Old English bob-tailed sheepdog, these are not big, square, sturdy and hairy, but more like the stars of [the] television programme, 'One Man and his Dog'--except that they are tailless...Their appearance is reminiscent of the old crossbred drover' dogs and cur-dogs depicted and described more than a hundred years ago. Like them, these bob-tailed dogs are alert, aggressive, fiercely protective and suspicious of strangers...The old drovers' route, when they moved livestock from mid-Wales to the Home Counties...is only a dozen miles from the farms where [these dogs] are employed Their herding instinct has been there for centuries. ("Bob-tailed Survivors in the Cur-Dog Tradition" by David Hancock, The Field, December, 1987.)

Above, "Drovers' Dogs" by Horlor, 1878

Hancock quotes Thomas Bewick's description of cur dogs:

...fiercer than the shepherd's dog; and their hair is smoother and shorter. They are mostly of a black and white colour; their ears are half-pricked; and many of them with short tails which seem as if they had been cut. They bite very keenly; and, as they always make their attack at the heels, the cattle have no defence against them; in this way, they are more than a match for a bull... (A General History of Quadrupeds, 1790.)

Left, a Scottish drover with his horse and dog by Sidney Cooper, 1891.

Left, a Scottish drover with his horse and dog by Sidney Cooper, 1891.

Bonser quotes Mary R. Mitford (Our Village, 1838), about a drover's dog called "Watch". Apparently, Watch, who was "black, with a little white about the muzzle, and one white ear, was as well known at fairs and markets as his Master...[and was] reknowned for keeping a flock together better than any shepherd's dog on the road..." Mitford describes how drovers' dogs were cared for: "Watch," she says, "like other sheepdogs [was] accustomed to live chiefly on bread and beer." Haldane says that "those who can still remember the last years of the droving period recall that the first concern of drovers on

arrival at houses or inns was food for the dogs", but Combe thinks otherwise. "The life expectancy of all droving dogs," she says, "was very short, due to sheer exhaustion, accidents and unfortunately sometimes ill-treatment and neglect...The men slept rough...but the dogs were constantly on duty keeping the flocks and herds together...The dogs had to fend for themselves or share in whatever the lurchers caught." Haldane points out that the harsh realities of life of a Scottish drover, which often required them to seek other employment

in the south or follow the harvest north before returning home, also forced them to abandon their dogs to their own devices:

Some years ago [a woman from] Brahan, Ross-shire, informed a friend that in the course of journeys by coach in the late autumn from Brahan to the South during her childhood about the year 1840 she used frequently to see collie dogs making their way north unaccompanied. On inquiring of her parents why these dogs were alone, [she] was informed that these were dogs belonging to drovers who had taken cattle to England and that when the droving was finished the drovers returned by boat to Scotland. To save the trouble and expense of their transport [her parents told her] the dogs were turned loose to find their own way north. It was explained that the dogs followed the route taken on the southward journey being fed at Inns or Farms where the drove had 'stanced' and that in the following year when the drovers were again on the way south, they paid for the food given to the dogs. No evidence has come to light that drovers returned from the South by boat, and it would seem that a possible alternative explanation is that the dogs belonged to drovers who had remained in the South through the autumn for the harvest when the dogs would not be needed.

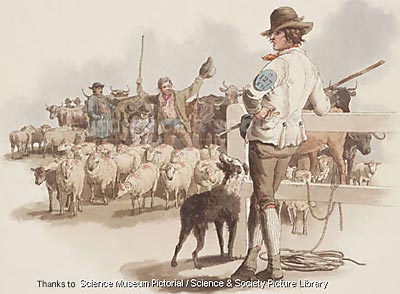

Right, "The Smithfield Drover", a painting by an unknown artist that often accompanies articles on droving. We are primarily interested in this painting because it shows the drovers dog. He is small, black and white, smooth-coated, and he has a docked tail. The drover himself wears his license on his sleeve, and looks rather like the cocky fellow described on the previous page. Both cattle and sheep have been brought to market.

For several hundred years at least, droving was an ordinary occurrence in the British countryside and an economic fact of life. "In the early 19th century," according to Bonser, "sheep began to predominate over cattle...[however], the droving trade continued to prosper in the nineteenth century as it had done in the eighteenth, until it began to give way to railway transport in the 1860s..." He goes on to say "It can be reckoned that there was little droving after the middle of the nineteenth century." However, particularly in more rural areas of northern Wales and Scotland, droving continued to some extent into the first half of the 20th century, where sheep still needed to be driven to railroad heads, local markets, and between summer and winter grazings. An article (first published in The Farming News Sheep Dog Supplement, August 1928 and reprinted inThe Kilmarnock Standard, October 1931) tells us what work was expected of a drover's dog in Scotland in the early part of the 20th century and what was their worth:

The ordinary drover's dog's business is on the roads...He goes ahead and blocks the side-roads, he keeps the flock in hand and sees they don't go too fast, he guards open garden gates. And he does it all so methodically, and without being told to do it, that one can see he is quite an expert in his business. At the gates of the cattle market one has often to get off the pavement so as not to check the out-flow of a big flock of sheep bolting into the roadway...The gateway that was jammed is only just cleared when out comes the [sheepdog] like a shot from a gun. Sometimes [it is] two dogs, bound on the same errand, to head the flock off and keep them standing still till they are told what road the sheep are to take. After them [comes] the drover, or the shepherd, quite leisurely. He signals to them, and one of the dogs comes to heel and the other goes on before, or else, according to orders, they bring the sheep down the road and off in another direction. They meet a motor car, and they drive the flock to one side of the road. They meet...anything...with a horse in the shafts, and they know that the driver will slow down to walking speed for his own sake...When one of the bitches casts a litter of puppies, the drover knows where he can get a pretty long price for every one of the family. They are all worth money for their inherent usefullness.

"Drover with Calves in a Country Cart" by Thomas Gainsboro, 1755.

In a BBC-Radio Scotland retrospective a few years ago, "In the Country: The Sheep Drovers", commentator Colin Miller interviewed men and women who were part of the droving tradition in Scotland in the first half of the 20th century. Miller tells us that "the early 1960s all but saw the end of a long tradition of sheep being traveled along the drove roads and highways by the drovers...moving them from farm and croft, to the livestock sales, or back and forth between summer and winter grazings. A fading tradition...[but still] alive...in the minds of the men and women who worked with the sheep not so very long ago..." Miller interviewed a women, Winifred Cooper, who bred blackface sheep on her farm in Aberdeen-shire, following the tradition of her father and grandfather. She recalled the shepherds they hired to move the sheep between the summer hill grazings and the lowland winter pastures. She said, "...they always had good dogs, of course..." John Bailey, a shepherd in Sutherland in the north, described how they would move the sheep and use their dogs to do it. "...We started driving slowly," he said, "let them go at their own pace, and let them feed, and they were putting weight on as they were going...We had to stay out most of the nights some nights to keep [the different flocks] separate...[we] kept the dogs going round [and] kept them walking and kind of keep them encircled [and] try and get them to settle down..." Another man, Charlie Brand, and his younger brother John, who, Miller says, "grew up beside the great Grampian drove route, called the Cairn o'Mount, [and were] droving hoggs [young ewes] from the glens of Perthshire down to winter on the Kincardineshire coast," gave an even more vivid account of their days of droving sheep between winter pastures:

We had verra guid (good) dogs [said Charlie] and verra guid tackity (tacked) boots...[John said] ye stayed wi' yer sheep from daylight to dark...ye had to be there, there was no fences...whenever the grass was finished they'd just move on themselves, ye see. Ye had tae be there, oh my, they wouldna wait for ye. [But, Charlie claimed the sheep] didna need much lookin after. Ye looked after them the first month--an' yer dogs was guid at that time--there'd be a dog maybe wide oot on the other side of the field walkin' back and forth, nay bother tae them...grand dogs at that time...If ye had a pair o'guid dogs ye could manage, but if ye hadna guid dogs...the sheep...could get awa wi' a lot. Ach, dogs was better at that time...That dog was oot every day and just ken't (knew) that job.

Trains may have hastened the demise of the long distance drover, but it was the increasing popularity of automobiles and trucks in the 1950s that all but put an end to droving and the drover's dog.

Copyright © 2009 by Carole L. Presberg

RETURN TO PART I

THE OTHER WEB PAGES WE MAINTAIN

These web pages are copyright ©2013

and maintained by webmeistress Carole Presberg

with technical help from webwizard David Presberg

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

If you are interested in using ANY material on this website, you MUST first ask for permission.